The people who’ve shaped the Sydney Opera House

This icon has been shaped by many. Here are seven people who have had a lasting impact.

The Sydney Opera House may have been sketched by one genius architect, but in the five decades since its opening, it has been shaped by hundreds. From the performers to the programmers, architects and the front-of-house team, so many have contributed to making the Opera House the extraordinary place we know today.

Although the sails have been a constant backdrop to Sydney since 1973, what happens inside is always evolving to reflect an ever-changing Australia. As the Sydney Opera House celebrates its 50th year, we look back and reflect on just some of the people who have helped define Australia’s favourite building.

Stephen Page

Artistic Director Bangarra Dance Theatre

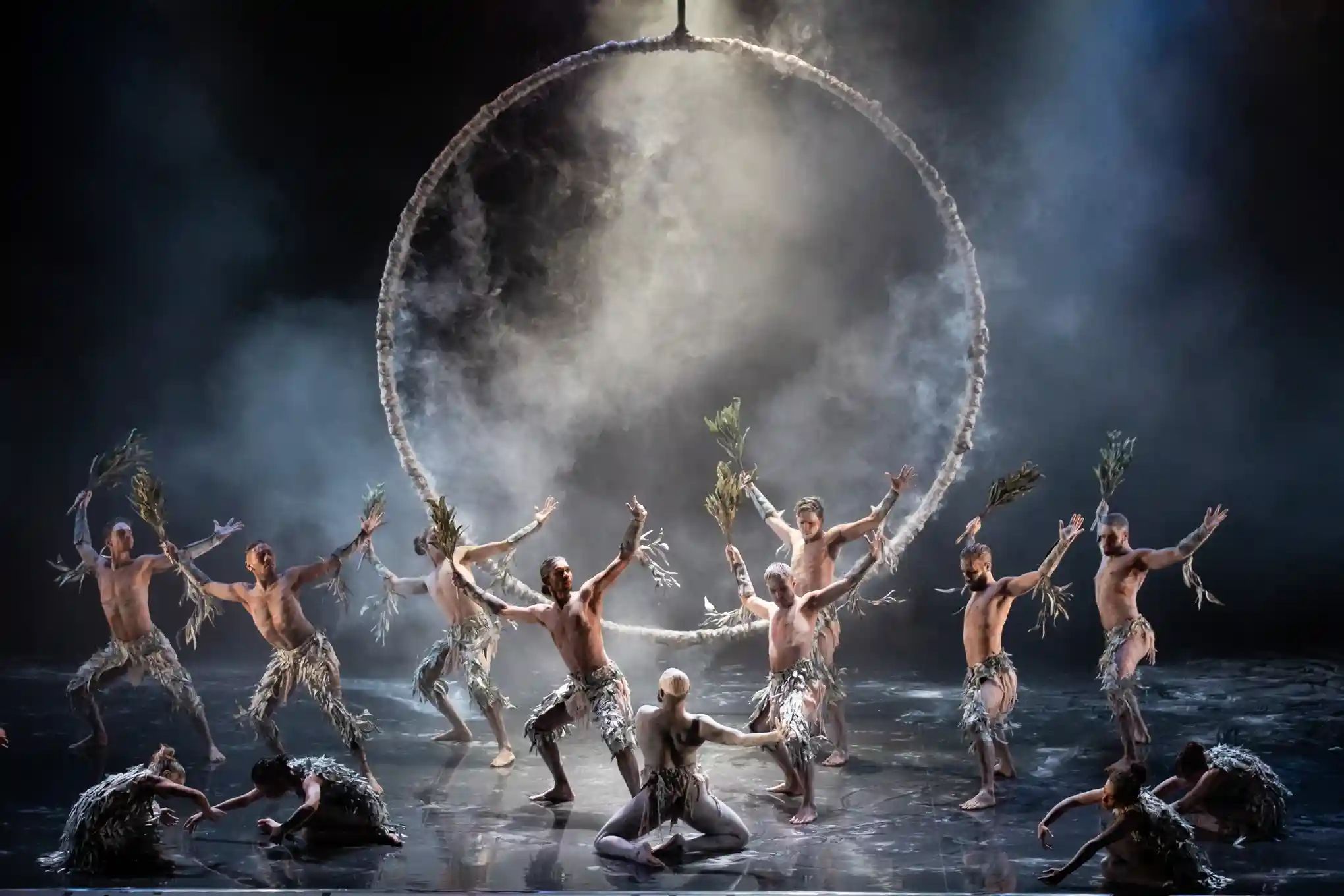

On winter nights as the sun sets behind the Sydney Harbour Bridge, the Western Foyers of the Sydney Opera House fill with people buzzing with anticipation. Inside, Bangarra Dance Theatre has captivated audiences with an intoxicating mix of traditional and modern dance and stories of the past and present. Each year, they leave those audiences hungry for the next new production from its visionary Artistic Director Stephen Page, and his talented team of dancers and creatives.

As one of the Opera House’s eight resident companies, Stephen says the Drama Theatre “feels like it’s Bangarra’s home. Having the Opera House as our stamping ground where we first tell our stories before they go out on Country and the world is a very significant relationship.”

Bangarra first performed at the Drama Theatre in 1997 with Fish, a work commissioned by Rhoda Roberts as director of the Festival of the Dreaming, but it did not become the dance company’s “home” until 2004.

Since then, the partnership has brought new, global audiences to Bangarra and made the Sydney Opera House unique among the cultural centres of the world: there are many ballet and opera companies - there is only one Bangarra.

“The fact that the Sydney Opera House has the leading performing arts company that's Indigenous is just great,” says Stephen, a descendant of the Nunukul people and the Munaldjali clan of the Yugambeh Nation from south-east Queensland. “What a beautiful fit!”

“I mean, imagine you’re a European and you’re going to a matinee and there's an Indigenous company and they’re programming Indigenous stories... you’d just go, ‘Wow!’”

Among his highlights as a resident company, Stephen lists Bangarra’s early productions, Fish, and Skin, which played at the Opera House in 2000, along with 2004’s Unaipon, choreographed by Associate Artistic Director, Kokatha woman Frances Rings.

“But then I think just recently Bennelong and Dark Emu were amazing in that space,” he says.

In 2023, Stephen will step down from the role he has held for more than three decades. He will be passing the baton to the current Associate Artistic Director, Frances, who he describes as “an exceptional dancer and a gifted and visionary choreographer”.

But Bangarra will remain at their “home” on Bennelong Point.

“The Opera House, like Bangarra, wants to speak to all people. If we’re iconic because we carry our heritage, the Opera House is because it has its contemporary heritage. Our work in that Drama Theatre was meant to be.”

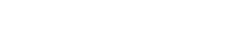

Bangarra Dance Theatre perform Bennelong under the artistic direction of Stephen Page. Image: Daniel Boud

Bangarra Dance Theatre perform Bennelong under the artistic direction of Stephen Page. Image: Daniel Boud

Kit Lee

Operations Manager, Sydney Opera House

When Kit Lee began working at the Sydney Opera House almost 50 years ago, audiences turned up to opening nights in floor-length evening gowns and tux and tails. Things are a bit more casual nowadays.

“I remember some came wearing a pair of thongs and I said, ‘Look, do you have a pair of shoes in your bag? If anything happens, if something falls onto your toes, we are liable!’”

As a former fashion student, she seems a little wistful for the elegance of the days gone by, and she laughs as she recalls the first Opera House uniform she wore in the 1970s - an embroidered minidress pinafore with a blouse underneath. “It’s still my favourite!” she says all these years later.

But as Operations Manager of the Opera House’s front-of-house team, it’s her job to make sure all patrons are taken care of – regardless of who they are or how they are dressed.

Kit began working at the Opera House in 1974, not long after it opened. The Hong Kong-born Queenslander had moved to Sydney after studying fashion, but found the industry was highly competitive and jobs were few. On a whim, she called the Opera House seeking work. One 20-minute interview later, she had gone onto the books as a casual.

Kit didn’t know it then, but she had found her second home.

As someone who likes people and likes to help them, Kit flourished in the front-of-house role and in 2000, she became theatre manager. It was her job to help make sure events ran smoothly so that patrons had an enjoyable experience. This included royalty including Queen Elizabeth and Prince Philip, but she says her “No 1” highlight was the visit by the Dalai Lama in 2002.

“He went to give a blessing on the stage and while we were going upstairs he put his hand on my arm and straight away I was in awe,” she says. “He was such a peaceful man, his energy just came to me. I still remember it gave me goosebumps.”

Kit is now in charge of 120 people. Over the past couple of years, through the trials of the pandemic, she says their job of making patrons feel at ease has become even more important.

“Since the lockdown we have found a lot of patrons have been a bit nervous. But they know that we're there to help them whenever we can."

Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II visits the Opera House

Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II visits the Opera House

Brian Eno

Curator of Luminous 2009

Brian Eno has spent his career pushing boundaries and exploring new territories. In 2009, he travelled to Australia to curate Luminous, a celebration of music, visual art, talks and performance at the Opera House.

For the visionary centrepiece of the festival, Brian combined technology and visual art to transform the graceful white sails into a canvas for a kaleidoscopic array of images that lit up the harbour and entranced the city. This was a first for the Opera House and the start of Vivid, an annual festival that has become a hallmark of Sydney’s Winter.

Brian’s goal was to make the events of Luminous “as seductive as possible,” he says. “I’m not into art being an existential challenge. What I want to make is something irresistible. Where you think, I’d really love to stay here for a while and look at this.”

Festival-goers could do just that at the Opera House’s Studio, where his installation 77 Million Paintings, an ever-changing image and sound installation he called “a club where nothing ever happens, slowly” played for 21 days during the festival.

The diverse live performance line-up ranged from talks and comedy, to experimental US rock group Battles and Seun Kuti, son of Afrobeat pioneer Fela, whose music, Brian says, “changed my life”.

Like Brian himself, all the artists on the Luminous line-up defied categorisation. "They are people who work in the new territories, the places in between, the places out at the edges,” he says. “Some of them take old forms and infuse them with new life, and make them new again, and others have invented forms of art that didn't previously exist."

Luminous created a blueprint for Vivid LIVE, a contemporary music festival of imagination, innovation and provocation. Over the years it has featured such trailblazers and cutting edge artists such as the Cure, Kraftwerk, Karen O, Anohni – and so many more.

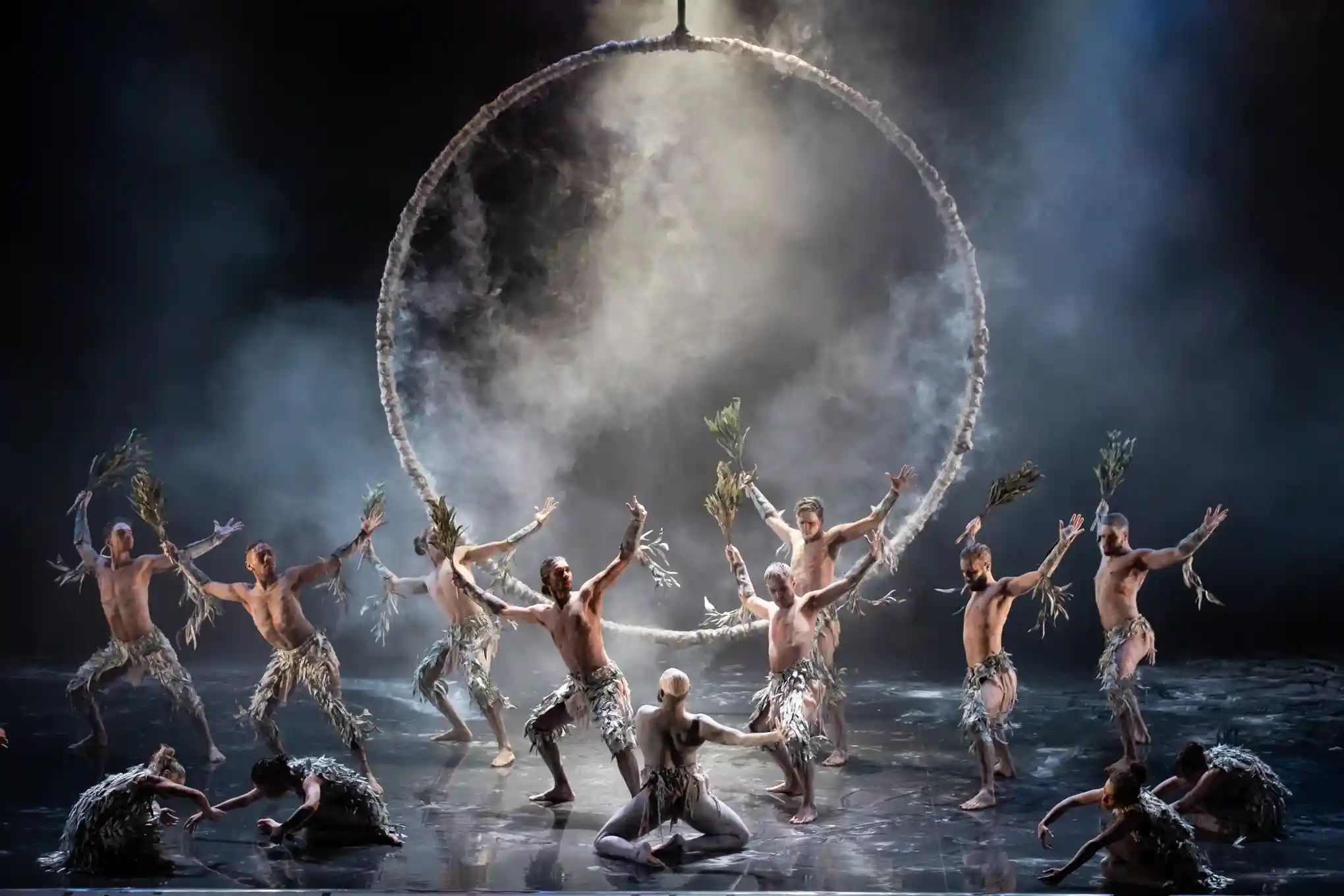

Brian Eno

Brian Eno

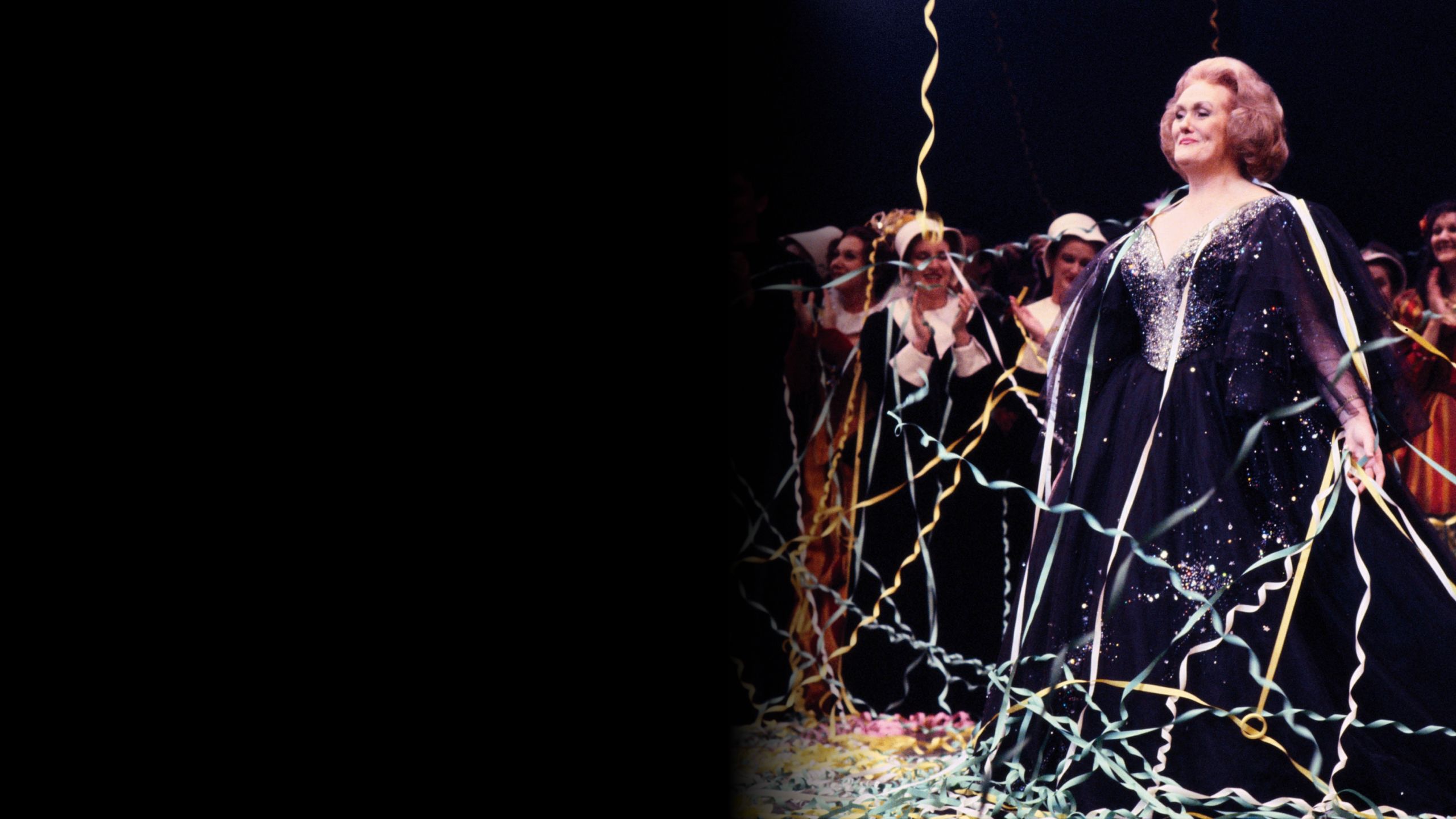

Dame Joan Sutherland

Grammy Award-winning Australian Soprano, performing from the 1950s - 1980s

Joan Sutherland made her first appearance at the Sydney Opera House in 1965. She was already an international star, but the Opera House itself was more than a decade away from its own international acclaim as one of the world’s iconic buildings.

The inauspicious occasion - the presenting of an award to a young local singer - took place in the unfinished Northern Foyer, where the wind off the harbour whipped through the tarpaulins covering the empty windows.

Almost a decade later, as the Opera House threw open its doors, Joan made her triumphant debut on the Opera Theatre stage, in Opera Australia’s Tales of Hoffman. It was the first of more than 250 performances at the House.

Over the next three decades, she held Sydney Opera House audiences spellbound with her pure coloratura soprano in performances that broke numerous box-office records, including a 1983 Concert Hall gala with Luciano Pavarotti that was broadcast live on the ABC to an estimated audience of 6 million.

Joan retired in 1991 at the age of 83. A year earlier, she gave her last full-length dramatic performance in her hometown at the Sydney Opera House. “Dame Joan was incandescent,” wrote The Age. “She gave a wondrous, full-voiced performance that should be remembered for light years to come.”

Joan’s career was studded with awards and accolades. In 1978, she was made Dame Commander of the Order of the British Empire (DBE) and in 2012, two years after her death, the Opera Theatre was renamed in her honour.

A portrait of Joan, painted by renowned artist Judy Cassab in 1976, hangs in the theatre’s foyer. Dressed in the rose-coloured robe and headdress of the title character from Delibes’ opera Lakmé, La Stupenda’s commanding gaze greets modern audience members as they file up the stairs, ready to be immersed in the wonder of live performance. A reminder of the magic and power of the performing arts, and the rich legacy of a once-in-a-lifetime star.

Dame Joan Sutherland cuts a slice of Opera House cake

Dame Joan Sutherland cuts a slice of Opera House cake

Rhoda Roberts

Head of First Nations Programming, 2012 - 2021

Rhoda Roberts says her time at the Opera House was “an absolute privilege”.

For nine years as head of First Nations programming – a role that was created for her – the proud Widjubal woman gave Indigenous artists a platform in the country’s leading arts centre to tell their stories across the cultural spectrum, in dance, music, visual art, theatre, and talks.

“I have to remind people,” she says, “that it is the first performing arts centre in this country – and indeed the world – that had a dedicated First Nations head of programming.”

“To have the power to have your own budget and actually decide what to do – it's very different to working under and with someone else's budget.”

This gave her an unprecedented autonomy to shape the First Nations program at the House and bring these works to larger, more diverse audiences.

Among the many and varied contributions, she initiated during her time in the role were ongoing events that are now centrepieces of Opera House programming, including Badu Gili, the nightly lighting of the sails that celebrates the work of First Nations artists, and Dance Rites, a groundbreaking competition she established to preserve the diversity of First Nations’ cultures and practices. The event, which is held in the Opera House forecourt each year, provides an opportunity to “reclaim and maintain the old Songlines for a new generation of performers learning from the old people”, she says.

Actress Deborah Mailman, herself now a trustee of the house, says Rhoda is “an amazing artist in her own right but she’s always seen the bigger picture. She’s been my champion as she’s been a champion for so many Indigenous artists.”

Rhoda, now an elder known to many as Aunty Rhoda, has stepped down from her role at the Opera House, but she is still working to champion First Nations artists.

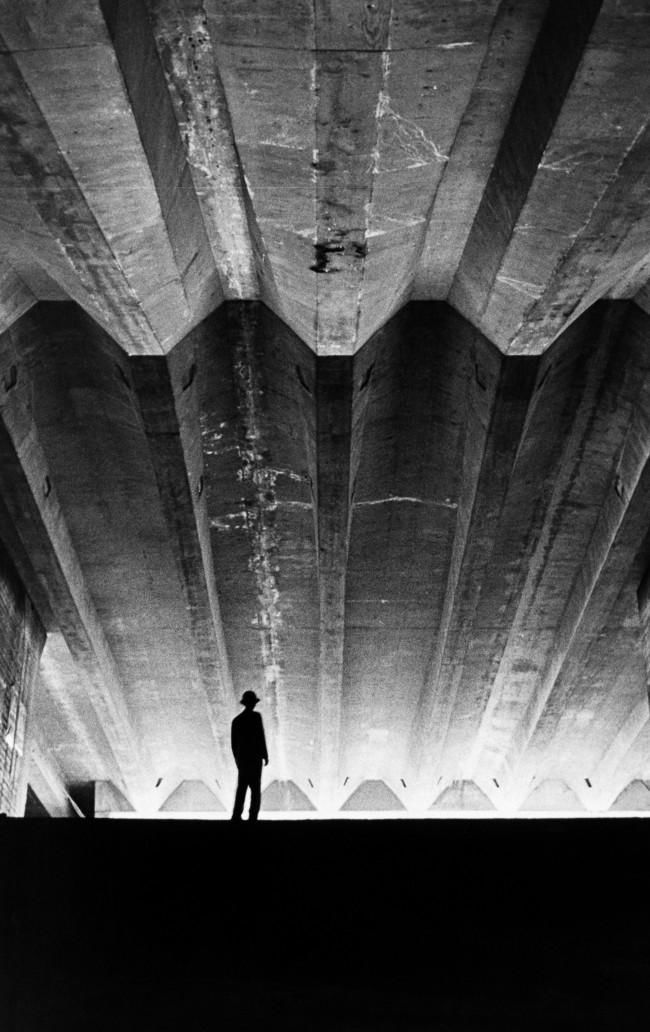

Homeground 2015. Image: Prudence Upton

Homeground 2015. Image: Prudence Upton

Alan Croker

Architect and author of the Sydney Opera House Conservation Management Plan

Every time Alan Croker goes to the Sydney Opera House, he finds a new space or angle he has never seen before. As principal architect with Design5, and author of the Opera House’s Conservation Management Plan (CMP), he says getting to know all the nooks and crannies in the sprawling site is “absolutely fundamental” to his job.

“Without knowing the building, we couldn’t honestly give guidance about it.”

Alan joined the Opera House as its heritage conservation architect in 2003 and five years later began revising the third CMP. The document is designed, he says, to provide guidelines on how to retain and respect Jørn Utzon's vision for the building.

Heritage conservation is critical, he says, because you’re “working with existing places and trying to make them work better. It’s an important aspect of sustainability and also environmental responsibility in the use of resources – you win on all levels, because you don't rip the pages out of history, you just sort of write a new chapter.”

The heritage architect and his team wrote a lot of chapters for the Opera House’s fourth CMP: it was 10 years in the making and runs to 300 pages long. The final document, which won a National Trust award, aims to be a handbook for maintenance, upgrades, refurbishments and day-to-day operations. Much of this work is unseen by visitors but is essential to the future of the house to preserve its status as a marvel of modern architecture and a cultural hub, both of which are recognised in its UNESCO World Heritage listing.

A longstanding patron, Alan laughs when asked about his most memorable experiences at the House, as if to say, “How long have you got?”, but nominates Bangarra’s Bennelong, a piece of “powerful storytelling” that held extra meaning for him given his research into the site where the Wangal man once lived. He is also still visibly moved by a performance of Mahler’s Resurrection symphony – a fitting choice for a heritage architect – by the Sydney Symphony Orchestra conducted by Stuart Challender in 1990.

“It was an incredibly moving concert. I found that I didn't want to leave the place after that performance. I just wanted to stay there and absorb the vibrations from that. The building was saying exactly the same thing as the music. It was extraordinary.”

The renewed Concert Hall

The renewed Concert Hall

Ann Mossop

Head of Talks and Ideas, 2010 - 2017

Pancakes, pasta and green prawn curry - with a side order of the Wiggles - was on the menu when Jamie Oliver took over the Sydney Opera House Concert Hall in 2015. In place of a drum kit or grand piano, a kitchen had been installed on the stage.

The celebrity chef spoke of the importance of healthy eating, while making his simple, delicious meals and cooking pancakes with children from the audience.

The event, held before a packed house of thousands, showed how eager people are to gather together to connect with ideas, as well as through music, theatre and more traditional performing arts.

These types of events are “a really important way to say the Opera House is for everyone,” says Ann Mossop, who was head of Talks and Ideas from 2010 to 2017.

But not so long ago, it wasn’t clear there was any interest in people going to see talks about anything much at all.

“What we have shown at the Opera House is that there is an audience and an audience of scale for that kind of thing,” she says. “You know, people might have said, ‘Oh, who will go and listen to a talk?’ Well, you know, it turns out quite a lot of people.”

Since Ann and her colleague Danielle Harvey set up All About Women 10 years ago, the annual festival of feminist talks has been attended by more than 72,000 people. Thousands have gathered at the Opera House for the Festival of Dangerous Ideas and Antidote, or to see one-off talks with economists, philosophers, architects, comedians and filmmakers: the range of topics that can be explored in this simple format is practically limitless.

Speakers during Ann’s time at the Opera House included teenage fashion maven, feminist and actor Tavi Gevinson, economist Thomas Piketty, martial arts film star Jackie Chan, Liberian Nobel Peace Prize winner Leymah Gbowee and a hologram of scientist Stephen Hawking. All these events provide an immediate and tangible connection between public figures and their audiences.

“There's an incredible pleasure in sharing the process of bringing ideas to life with some of these amazing people,” Ann says, “whether it's a scientist, a philosopher, somebody from the world of film and television. There's something magical about the live experience.”

Stop Fixing Women with Yassmin Abdel-Magied, Catherine Fox, Ann Sherry and Fauziah Ibrahim at All About Women, 2017. Image: Prudence Upton

Stop Fixing Women with Yassmin Abdel-Magied, Catherine Fox, Ann Sherry and Fauziah Ibrahim at All About Women, 2017. Image: Prudence Upton

Celebrate the extraordinary

In our 50th year, we’re throwing a party and everyone’s invited. Join us for a year-long festival celebrating the past, present and future of Australia’s favourite building.

Explore our 50th Anniversary program.