Sydney Opera House to scale

A visual story about ambition and imagination

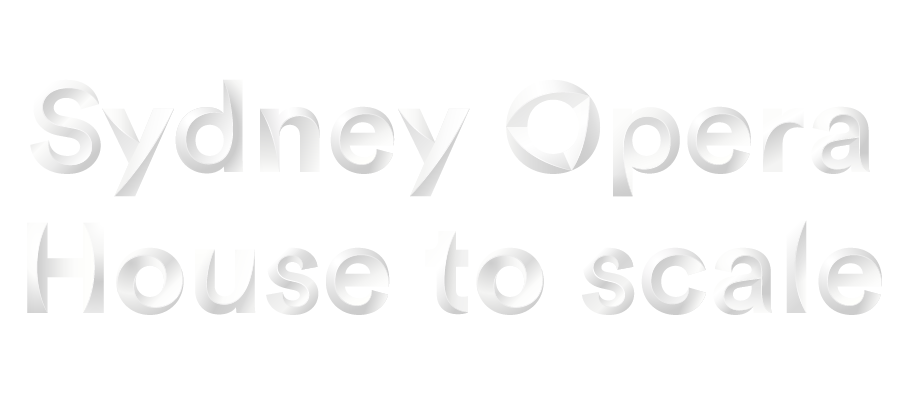

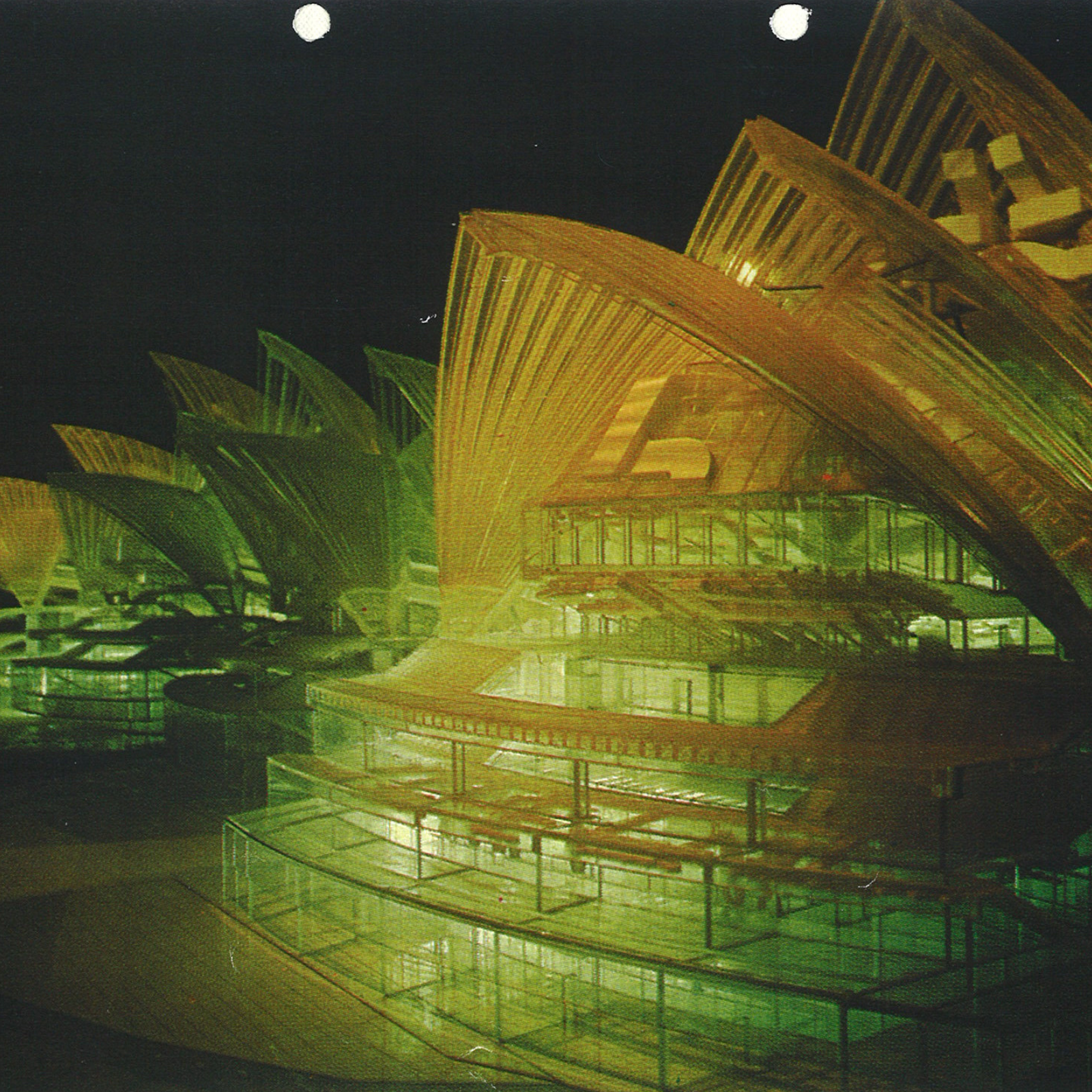

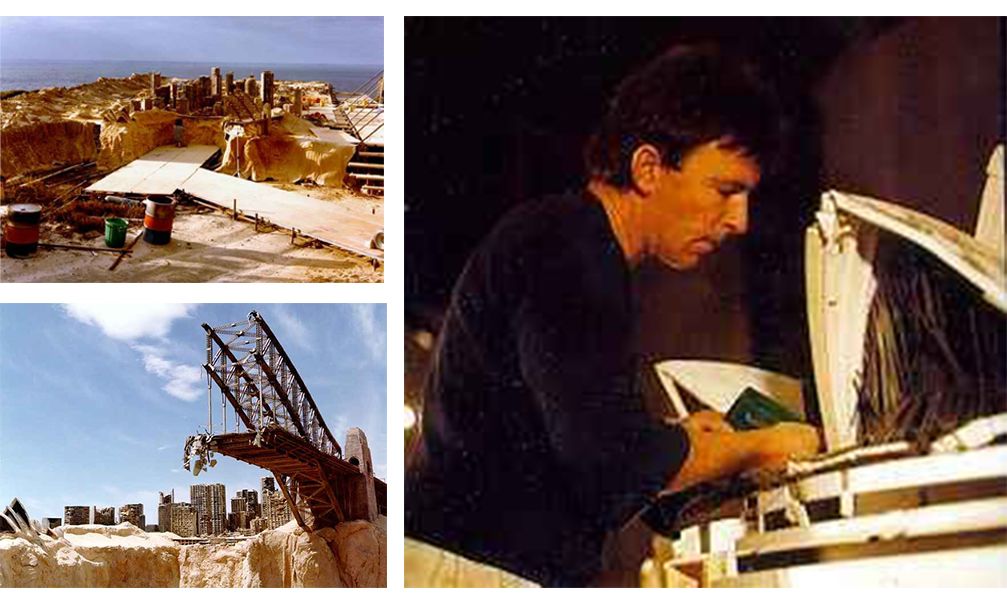

Building the Opera House was unimaginably difficult. It took incredible feats of design and engineering to bring Jørn Utzon’s plans to life, and many turbulent years. A methodical process of trial and error, it demanded a multitude of sketches and models.

Image: Powerhouse Museum

Image: Powerhouse Museum

Nowadays, to build the Opera House is a feat of careful replication. The maker is challenged to master the specific angles and curvature of the sails, to replicate that faint off-white glow that shines over Bennelong Point.

Some attempts are more flattering than others.

Image: @daningham

Image: @daningham

Utzon’s Sydney Opera House project was shrouded in a sense of impossibility, a feeling that the aspirations of this building were too lofty for an unassuming city like ours. By pieces or pixels, the most effective models of the Opera House convey that feeling. These are some of our favourites.

Models for replication

The Crystal Palace

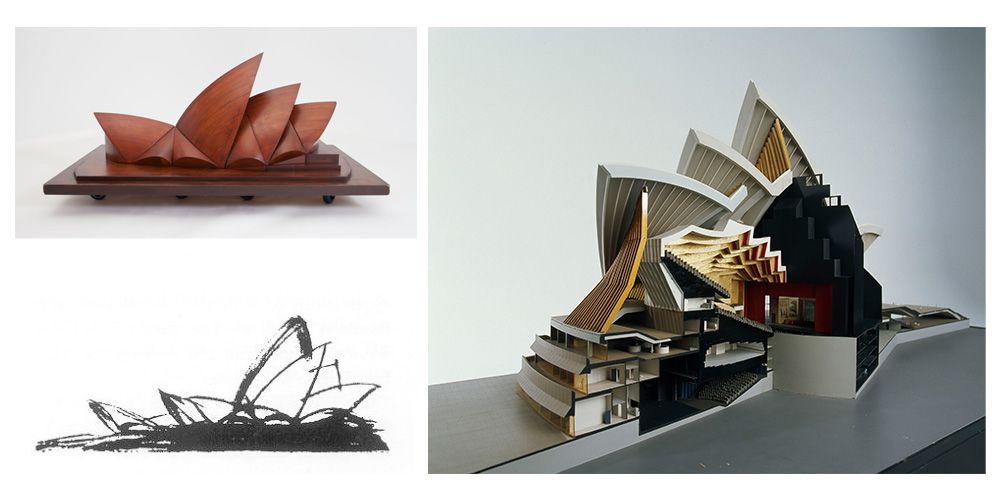

One of the best known to-scale models of the Opera House was built by industrial modelmaker Bill Lambert and nicknamed ‘The Crystal Palace’. Originally commissioned by the Department of Public Works after Utzon resigned in 1966, it was to serve as a perfect miniature of the building and was based on Utzon’s many thousands of sketches.

Bill Lambert pictured building the Crystal Palace (left) and Bill's daughter Christine Pettinger with the reassembled model in 2006 (right).

Bill Lambert pictured building the Crystal Palace (left) and Bill's daughter Christine Pettinger with the reassembled model in 2006 (right).

The model was comprised of 2000 pieces, and would sit at 4.5 metres long, three metres wide and 1.8 metres high. It was made with Perspex, a semi-transparent acrylic able to be shaped when heated, and was intended as an instrument for testing the heating, cooling and ventilation of the building – something more easily achieved with computer modeling these days.

Its fate echoes that of the original. Like Utzon, Mr Lambert was never able to entirely complete his opus. The government withdrew funding in 1973, the year the Opera House itself was finished. Lambert’s daughter Christine Pettinger told the Sydney Morning Herald that the model “absolutely consumed his life”.

“He lived it and he slept it.”

The Crystal Palace was briefly displayed in its incomplete state at international exhibitions before being stored away for 30 years. Rediscovered in 2002, it was handed back to the Opera House Trust, before being put on display in Customs House, then once again disassembled.

This was not Lambert’s first dally with the Opera House. His company was also responsible for the 1:200 cast resin model pictured below. Made in 1958-1959, the model is notably flatter than the completed building, as it represents the first version of the roof design. According to the Museum of Applied Arts & Sciences, this model was created to “publicise the Opera House project and help raise funds for it via a public appeal”.

Image: Museum of Applied Arts & Sciences

Image: Museum of Applied Arts & Sciences

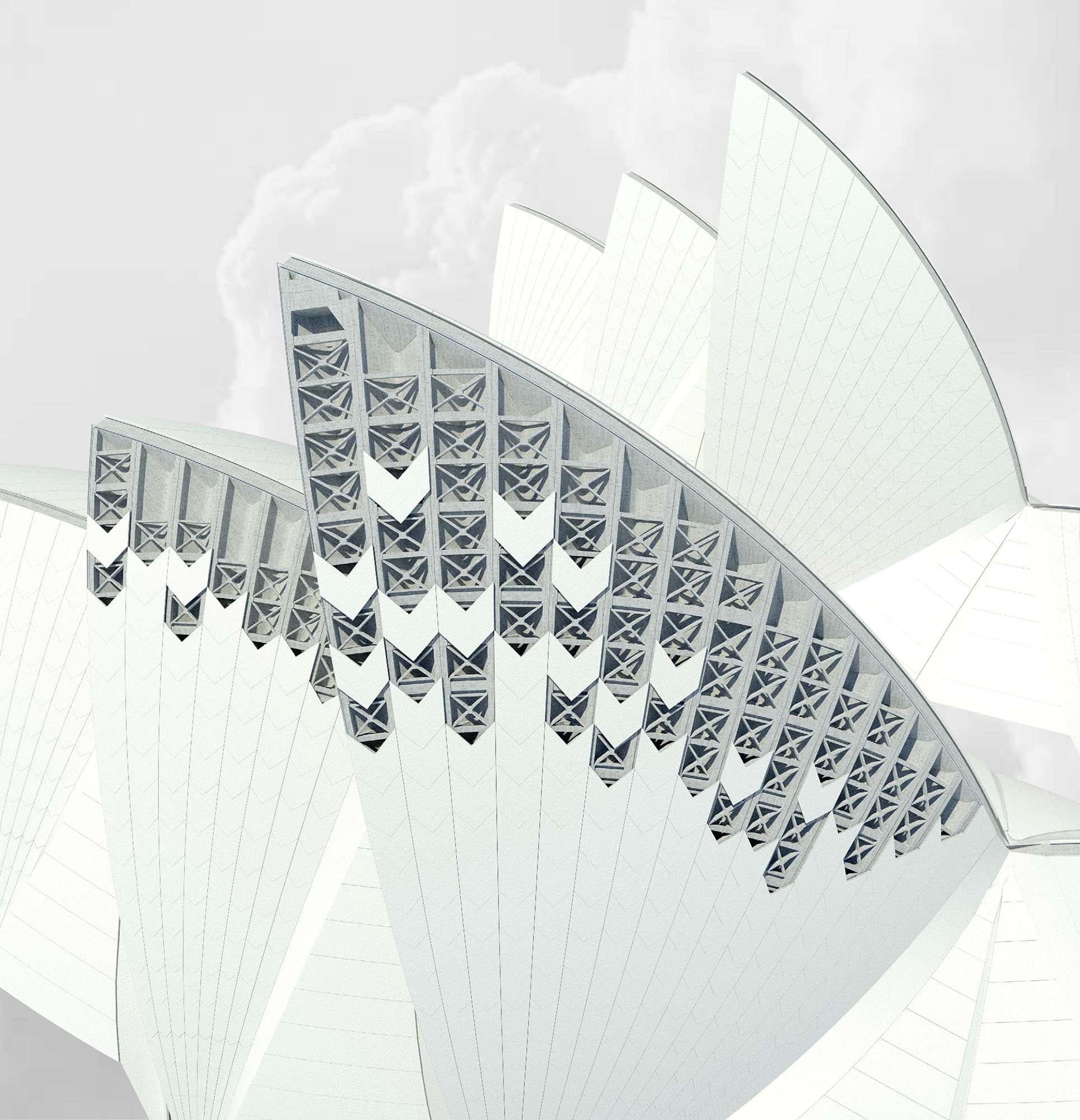

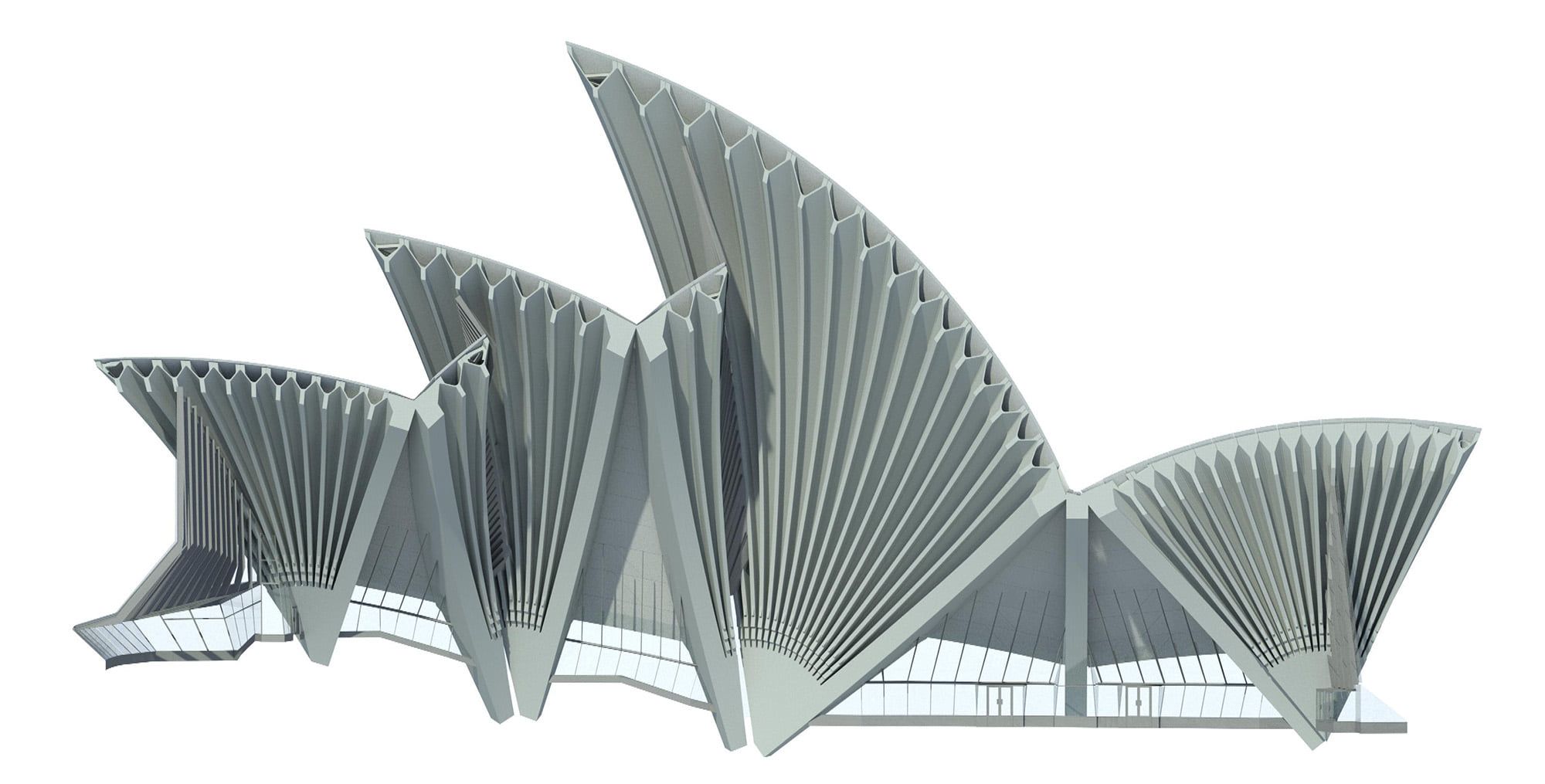

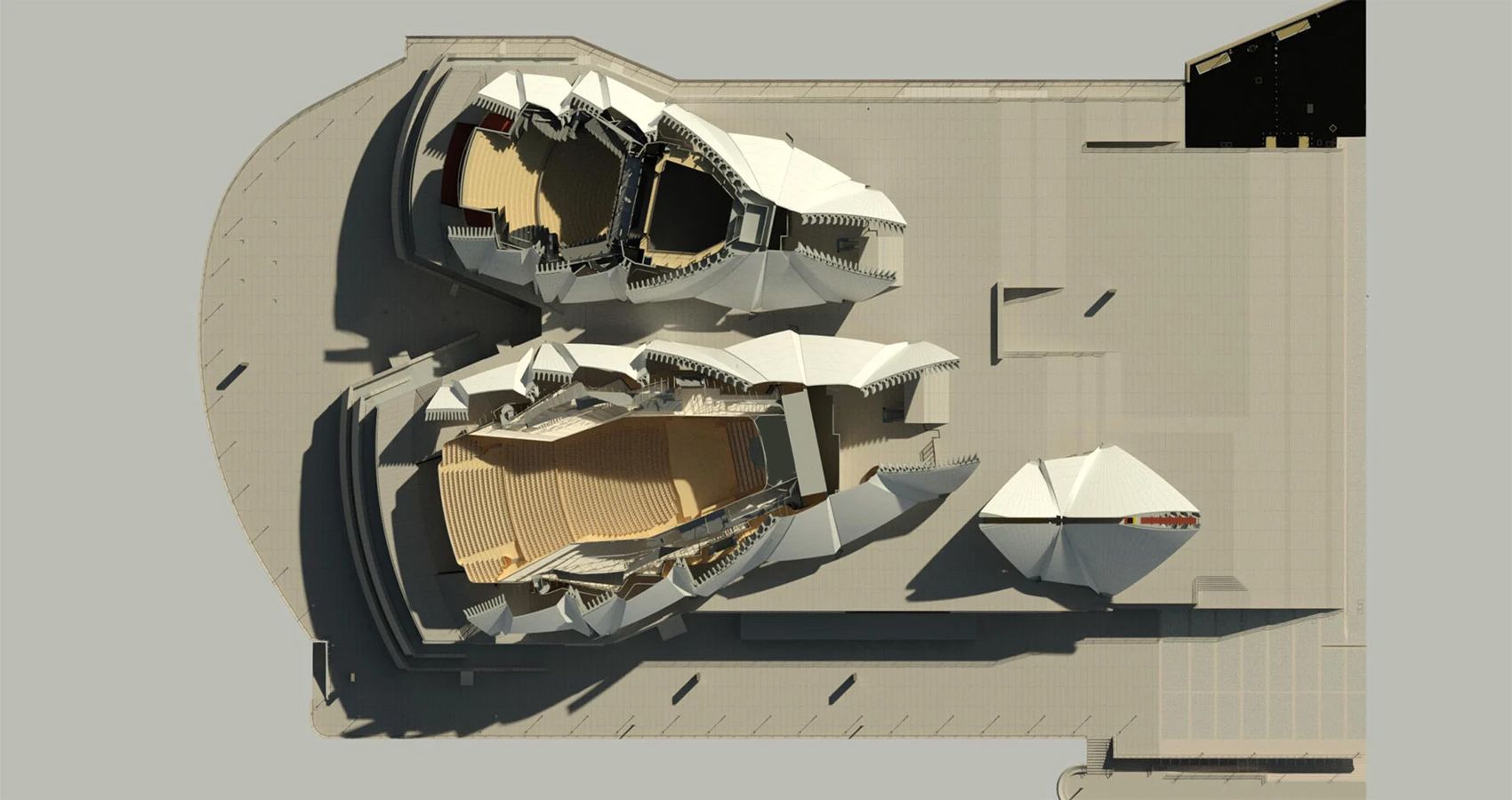

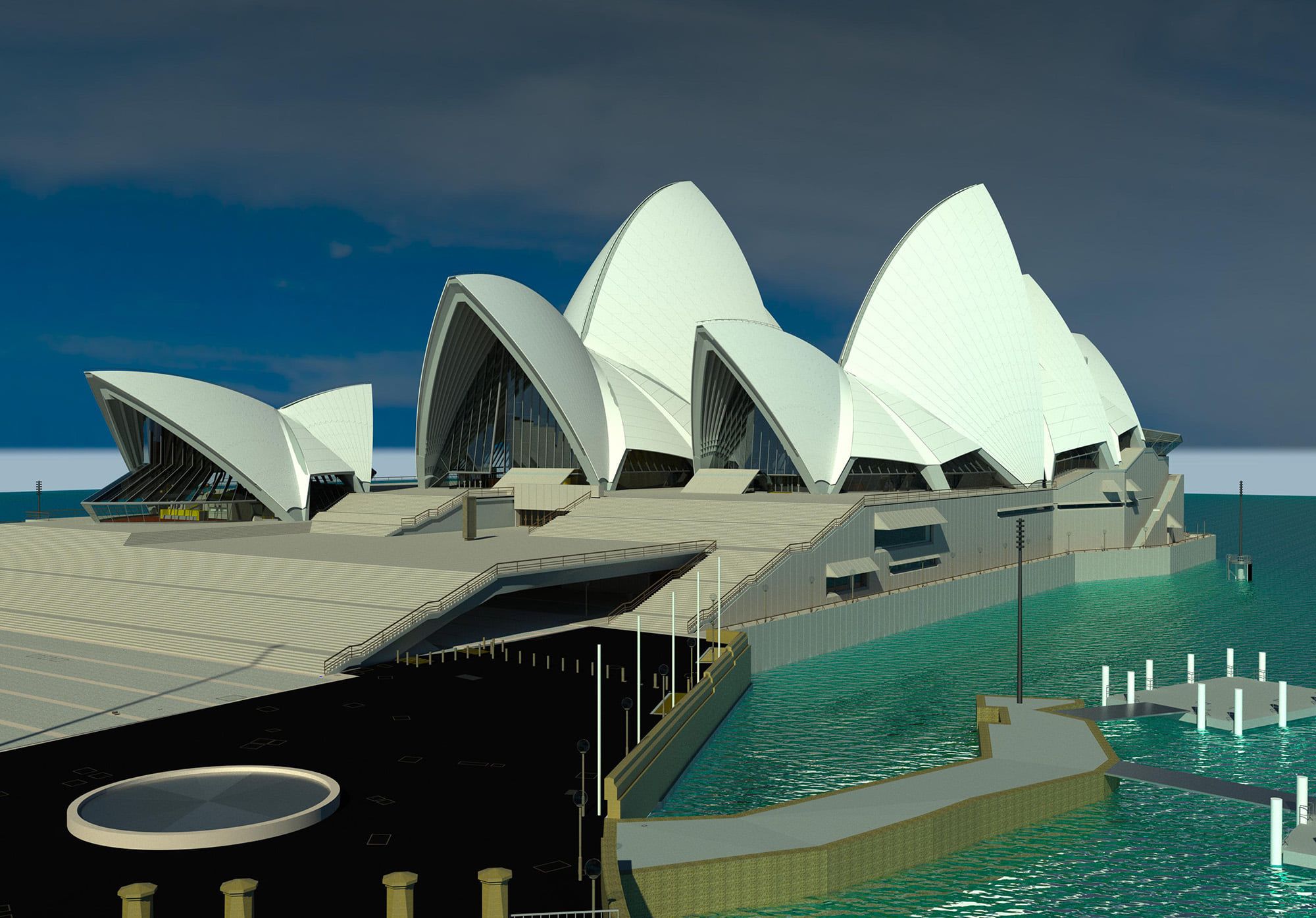

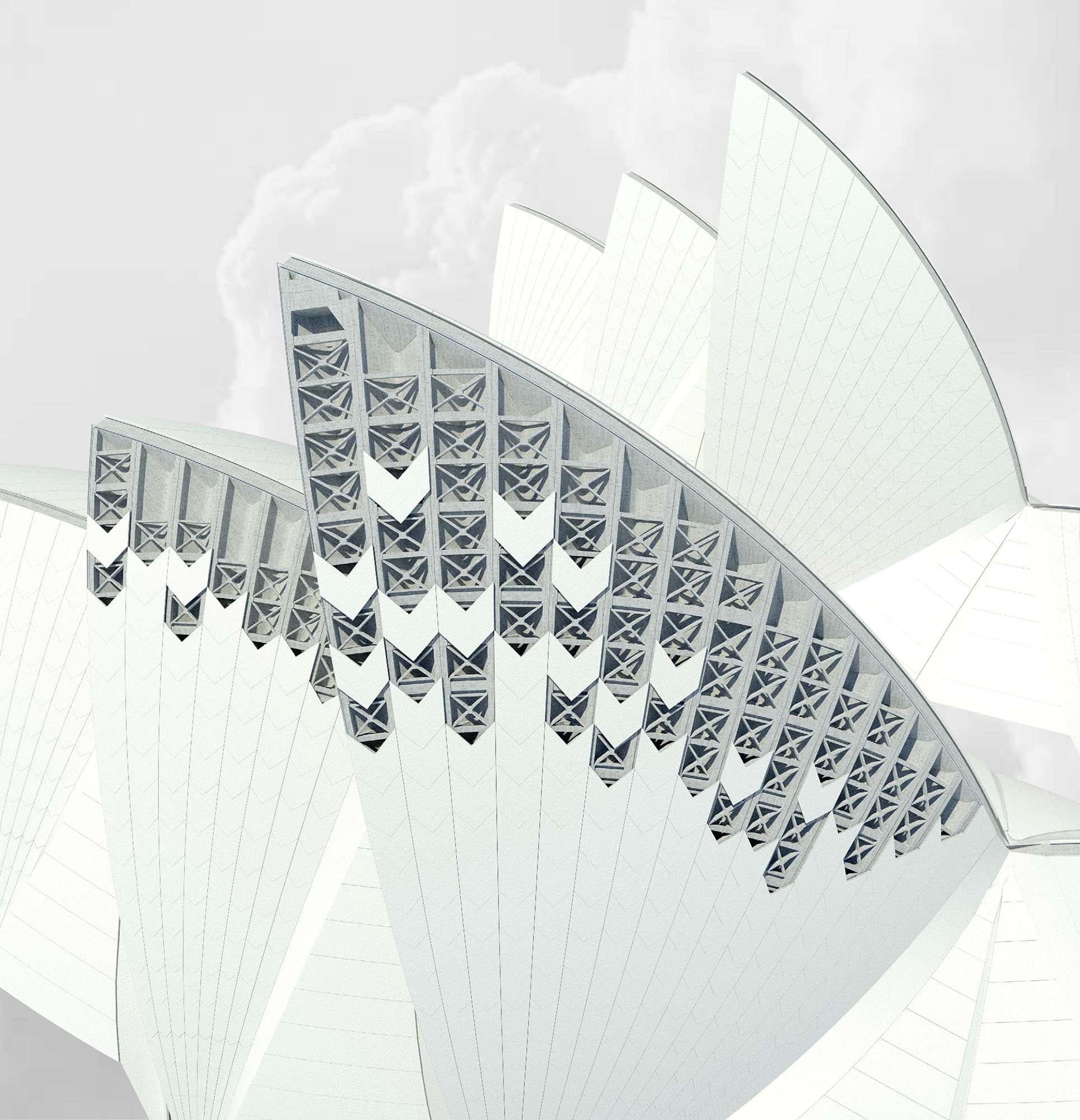

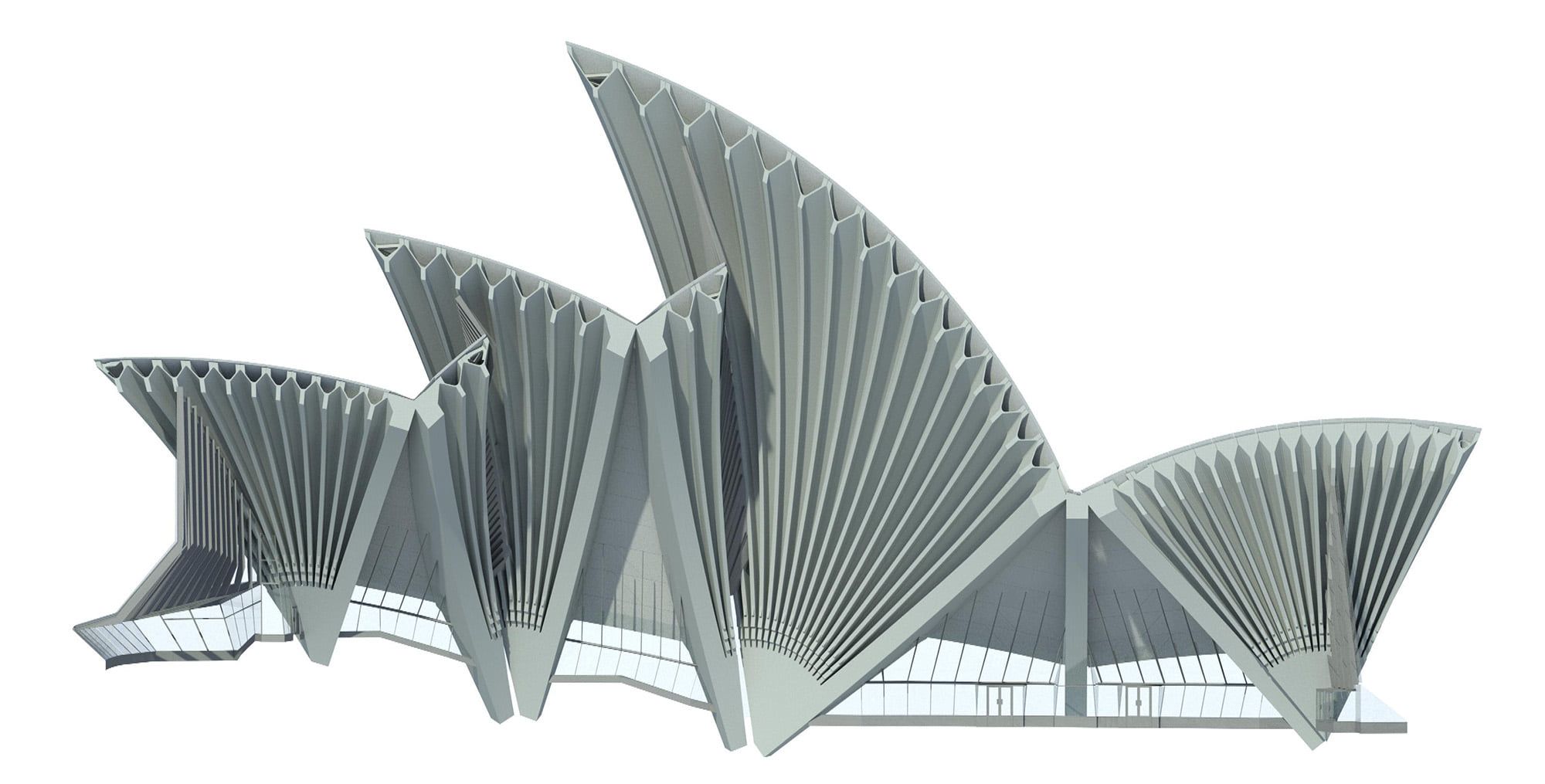

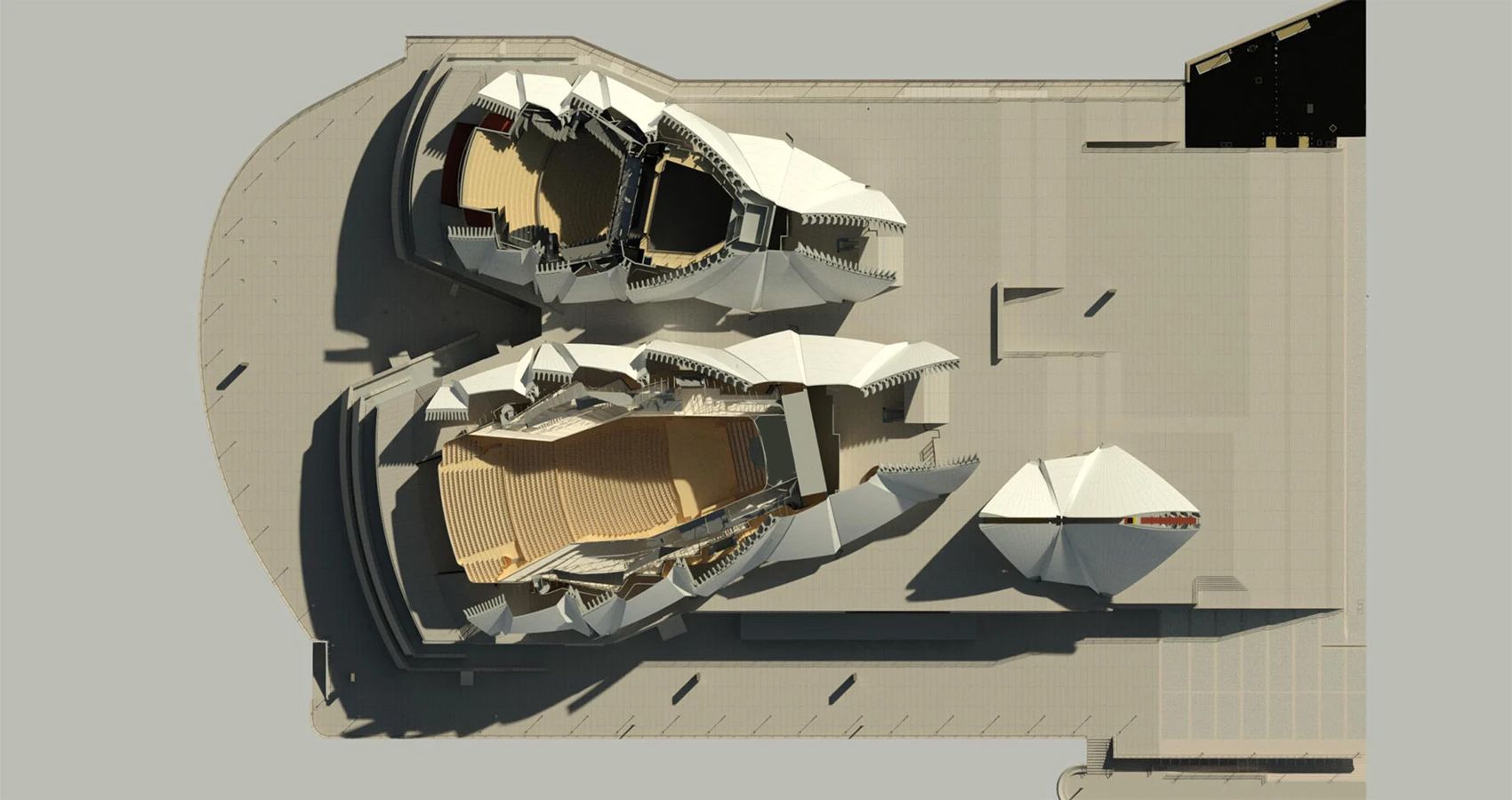

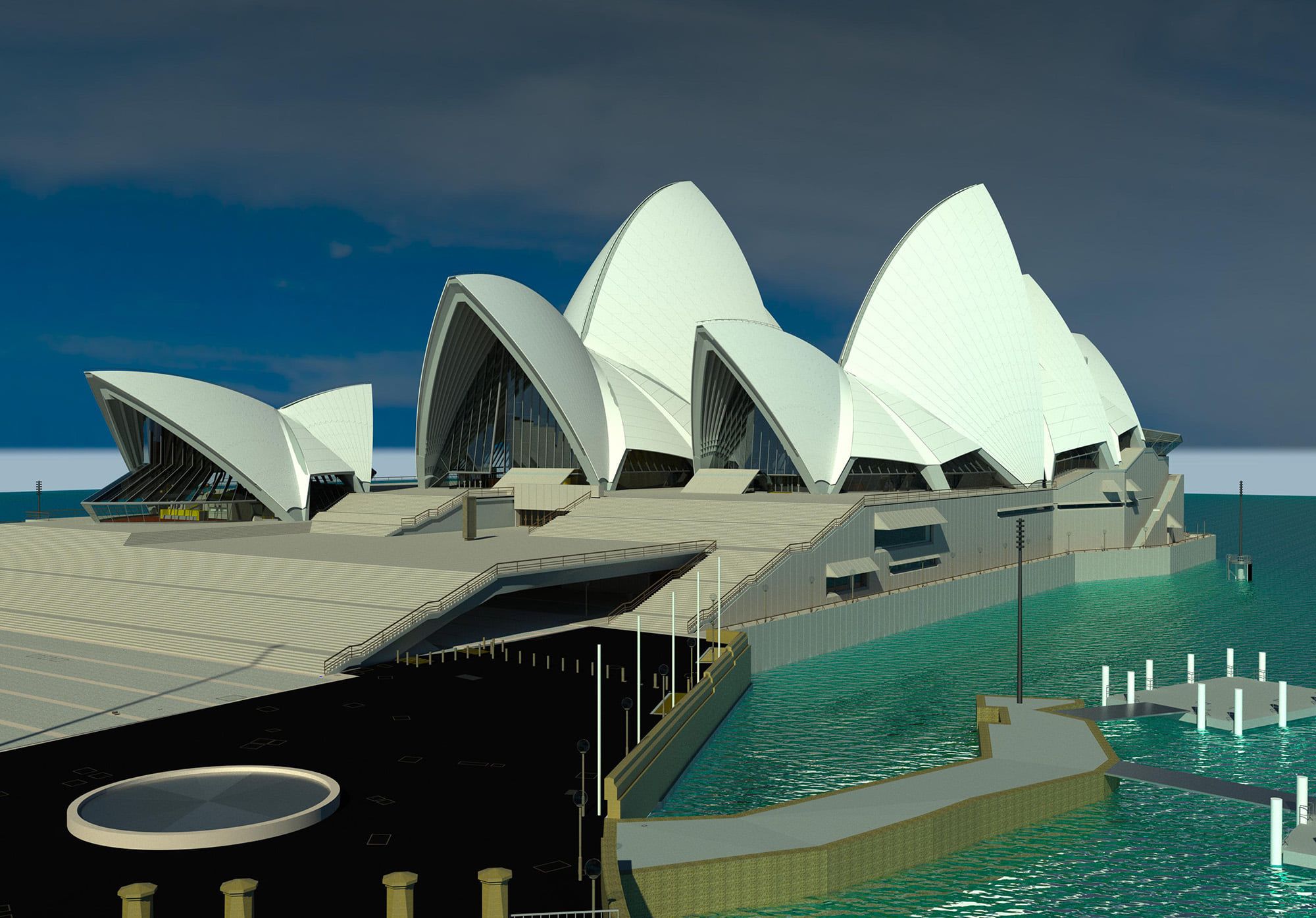

The Digital Twin

A digital successor of sorts to the Crystal Palace, the Sydney Opera House’s Building Information team have spent the last six years developing a series of digital scale models of the Opera House and the immediate precinct.

Their goal resembles Mr Lambert’s: to create a complete digital replicate of the Opera House. This ‘Digital Twin’ will serve myriad functions: assisting construction and maintenance projects, conservation, events, asset management, security and more.

“The models will eventually form the building blocks for future interactive plans, models and virtual environments, effectively anything that could benefit from 3D geometry,” explains Building Information Manager Steven Lianos.

Models for movies

Mad Max miniature

The Sydney Opera House is no stranger to the silver screen – regularly offered up as visual shorthand for ‘international destruction’. While this usually involves CGI and special effects, it’s very occasionally the product of modelling and miniatures.

Mad Max: Beyond Thunderdome was the third film in George Miller’s post-apocalyptic series. As the film ends, we follow Jedediah the Pilot flying the Lost Tribe over a decimated Sydney city (the fabled ‘Tomorrow-Morrow Land’) that’s shrouded in red dust – creepily reminiscent of the city during the 2020 bushfires. It’s one of the most impressive shots of a visually-stunning film, showing a collapsed Harbour Bridge and an irradiated Sydney engulfed in sand.

Though appearing only fleetingly, these architectural replicas were painstakingly built by model coordinator Dennis Nicholson and his team. Scorched, hollow skyscrapers surround the Opera House, which pokes out of the dried-up harbour like a crustacean.

Sadly, as is proving a common theme, the models were too big to keep around and were promptly destroyed after filming.

Mad Max: Beyond Thunderdome (1985)

Models for orientation

The Sydney replica

Few cities in the world are as instantly identifiable as Sydney. And yet, Sydney’s is a rare cityscape not defined by its skyline. The iconic image of Sydney is not of a silhouette staircase of high rises, but of the Opera House sprouting from Bennelong Point, enclosed by a blue harbour and flanked by the Harbour Bridge. These icons guide our orientation, and to recreate Sydney is to first recreate these icons.

The Sydney replica that lives enclosed in glass underneath the floor of Customs House was made by Modelcraft in 1999. At 1:500 it measures 4.2 by 9.5 metres and was valued at $1 million. It was built as a tourist and information tool during the Olympics tourism boom before a stint on the fourth floor of Customs House and then some time in storage. Nowadays it lives on under the feet of patrons of the Circular Quay landmark – a colourful recreation of the city you're standing smack in the middle of.

Sydney city to-scale miniatures underneath a glass floor in Customs House

Sydney city to-scale miniatures underneath a glass floor in Customs House

Models for touching

Tactile model

During Audio Described tours of the Opera House, tour guide Steve McAuley often incorporates tactile elements, using small models of the Opera House to allow vision impaired visitors to feel the shape of the building.

“We have two models we use for tactile experiences. People who are blind or have low vision are able to touch the model to supplement the audio descriptions they are being provided to get a better understanding of the shape of the Sydney Opera House and the layout of the site,” explains the Opera House’s Accessibility Manager Janelle Ryan.

“The simple lamp is used to give people an idea of the shape of the sails. The smaller site model gives more context of the layout of the building.”

The Opera House accessibility team is also in the process of procuring an additional 3D plastic printed model of the building for future use in tactile tours.

On a pedestal near the entry to the Opera House’s Box Office foyers is another tactile experience: a series of bronze panels showcasing Utzon’s Spherical Solution. Discoloured by the many millions of hands that have felt it, this staple of the Opera House experience was unveiled in 1993 by Lin Utzon to commemorate her father’s ingenious design solution that attained “full harmony between all the shapes in this fantastic complex”.

Models for gaming

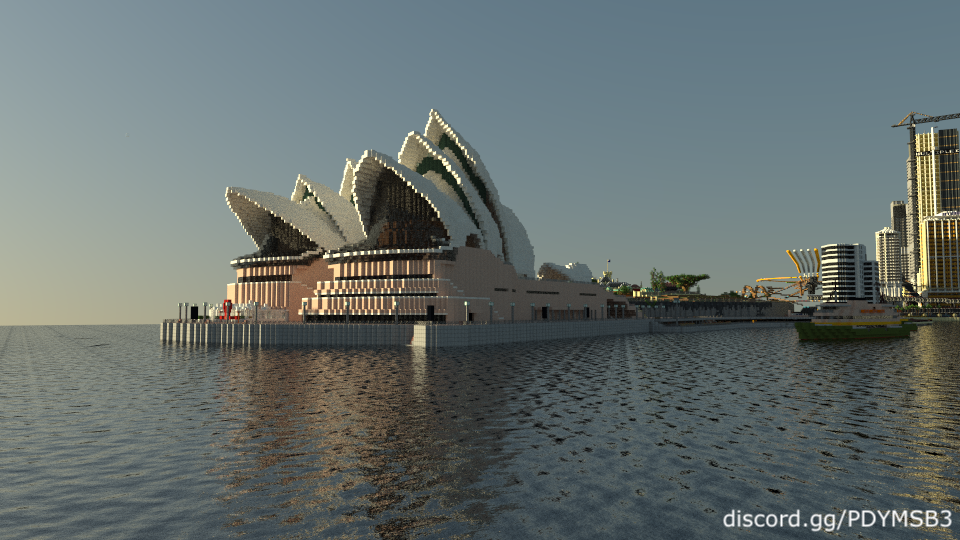

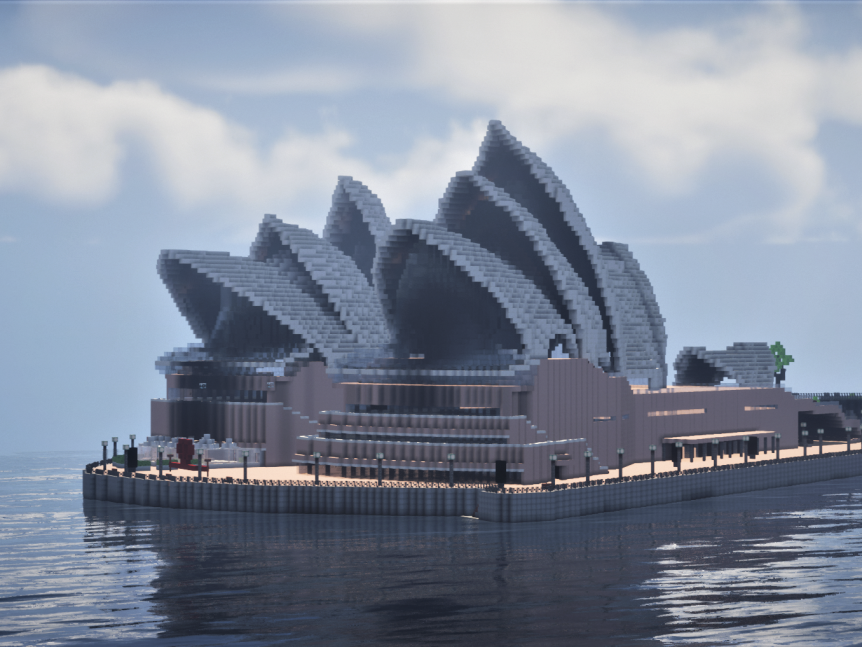

Minecraft

Earlier this year, a worldwide crew of 1600 Minecrafters started the Build the Earth project, an attempt to recreate the planet in 1:1 scale in the beloved sandbox game. Among the starting destinations was Sydney Harbour.

“As the Sydney Opera House is an iconic emblem of Sydney’s architecture, it was important that we were incredibly precise, detailed and patient,” Build the Earth collaborator Aren Zouain told the Sydney Morning Herald.

The Build the Earth project relies on modifications that use Google Maps and other geographical data archives to generate terrain. But more complex locations, like landmarks, require build teams. These teams use ‘hub servers’ to collaborate and once significant progress has been made they merge their world files to the master world.

Launched by YouTuber PippenFPS during the early months of the Covid-19 pandemic, Build the Earth Minecrafters had a shared ambition to bring alive the world that we can’t presently explore.

“...to be born in this time period allows us, for the first time in human history, to see the majesty of our birthplace in its totality.”

The Opera House was one of the first projects completed by the Oceania Build Team.

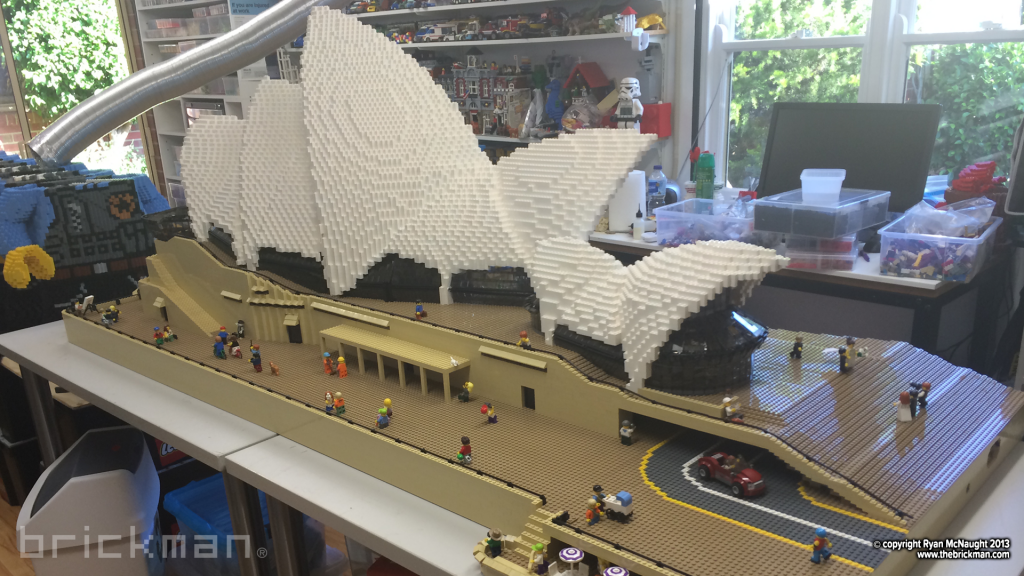

Brickman’s LEGO® model

LEGO® Masters fans will be familiar with Australia’s only Lego certified Professional Ryan ‘The Brickman’ McNaught.

Back in 2013, McNaught took on his “own personal Mount Everest”: building the Sydney Opera House. The Brickman made it even more difficult for himself by constructing a cutaway interior. Delve inside and you’ll spot a few Easter eggs for Australian fans, including a tiny Peter Allen performing on the Concert Hall stage.

Like Utzon, McNaught was stumped by the curvature of the sails, eventually bringing on US Master Builder Erik Varszegi and consulting LEGO’s Digital Designer program. In all, the project required 75,000 pieces and was actually one of two times the Brickman took on the Sydney icon.

In 2015, for the Sydney Museum’s Sydney Harbour exhibit, he faced Everest once again, but this time doubling the size of his model. McNaught explains below that if you’ve done it once, the second attempt is easy, perhaps unlike Everest.

Brickman's first Opera House build. Image: Ryan McNaught (2013)

Brickman's first Opera House build. Image: Ryan McNaught (2013)

Cutaway interior featuring Peter Allen performing on the Concert Hall stage. Image: Ryan McNaught (2013)

Cutaway interior featuring Peter Allen performing on the Concert Hall stage. Image: Ryan McNaught (2013)

Attempt two, double the size. Image: Ryan McNaught (2015)

Attempt two, double the size. Image: Ryan McNaught (2015)

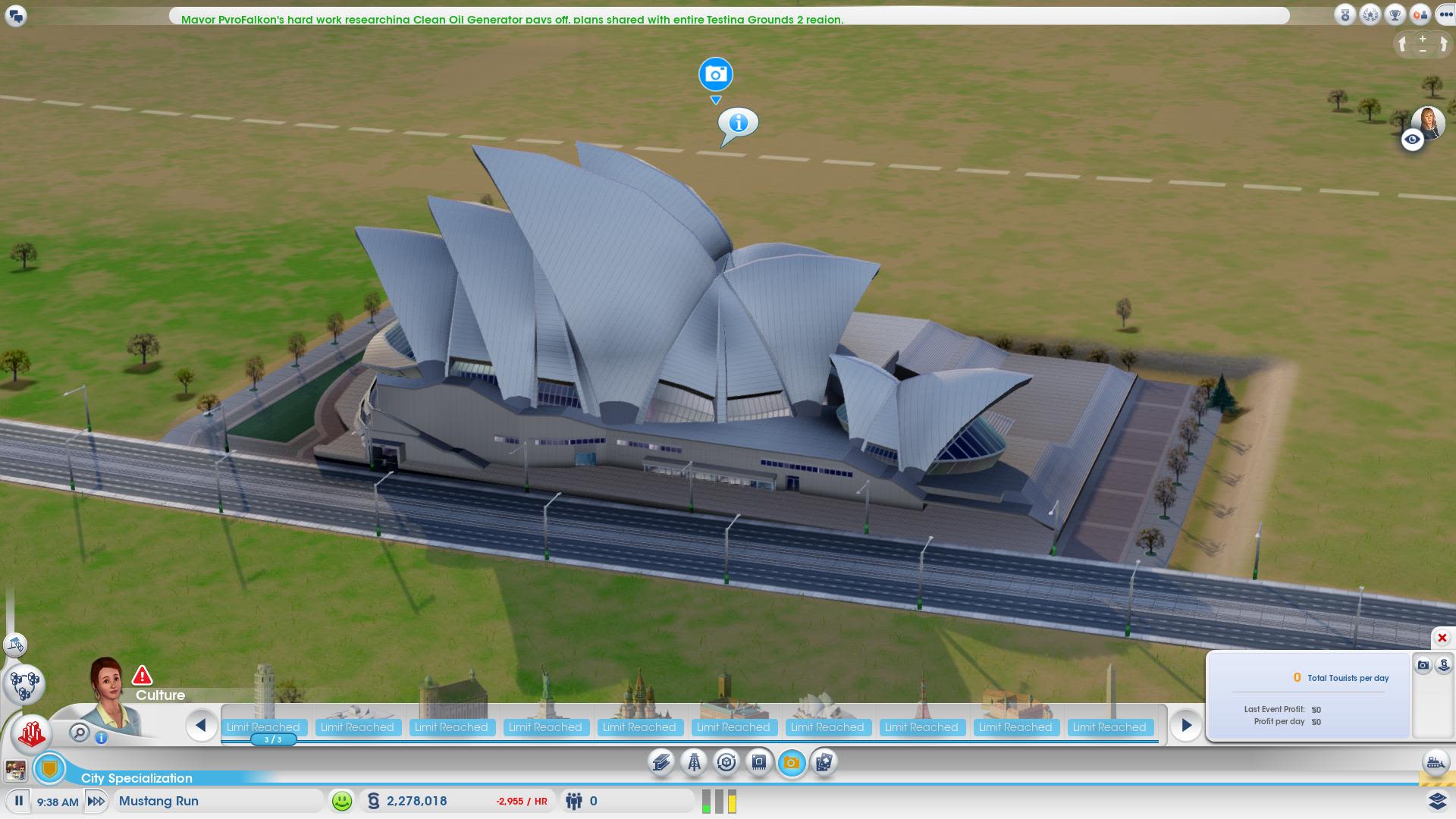

Video games

Minecraft is chief among a suite of modern ‘sandbox’ games – video games that emphasise free design and minimal rules, allowing the player to “produce a world from sand”. You can put anything you want in these worlds of sand, including, in some cases, the Sydney Opera House.

A roadside Sydney Opera House in 'SimCity' (2013)

A roadside Sydney Opera House in 'SimCity' (2013)

But not all are entirely lawless. Popular strategy game Civilization VI stipulates that the ‘Atomic Era Wonder’ Sydney Opera House “must be built on the coast, adjacent to land and a harbor”. Building the Opera House in Civilization VI gives the player “+8 Culture, +5 Great Musician points per turn and +3 Great Works of Music slots”.

The Opera House in 'Civilization VI' (2016). It must be built on the coast, adjacent to land and a harbour. It cannot be built on a lake.

The Opera House in 'Civilization VI' (2016). It must be built on the coast, adjacent to land and a harbour. It cannot be built on a lake.

Other games, like the recent Microsoft Flight Simulator (2020), use world icons as a tool of localisation. Flight Simulator has rebuilt the entire planet using textures and data from Bing maps while recreating photorealistic models of buildings and terrain with AI technology, including a faithful Opera House.

The Harbour Bridge was not so lucky, noticeably stripped it of its famous arch and pylons. Thankfully, independent Australian developer Orbyx have released an update that recreates 100 points of interest across the game, including the Harbour Bridge in photorealistic detail.

Sydney with a truncated Harbour Bridge, as featured in 'Flight Simulator' (2020)

Sydney with a truncated Harbour Bridge, as featured in 'Flight Simulator' (2020)

The Opera House in 'Command & Conquer: Red Alert 2', in a mission entitled 'Clones Down Under'

The Opera House in 'Command & Conquer: Red Alert 2', in a mission entitled 'Clones Down Under'

The Sydney Opera House has taken many forms over the years. No longer just an heirloom for us lucky Sydneysiders, this once-impossible building has materialised over a spectrum of mediums. And whether on a miniature movie set or in a digital sandbox, it remains a perfect symbol of ambition and imagination.