Stage Direction:

Cry-Baby

A camp musical set in the 1950s from cinema’s ‘Pope of Trash’, John Waters’ Cry-Baby has endured as a cult classic. Elfy Scott follows the film's complicated journey from screen to stage.

Speaking to documentary-creator Mark Rance in 2005, John Waters reflected on the legacy of Cry-Baby, as compared to his earlier creations.

“Everyone thinks Hairspray was my big musical because it’s a big Broadway musical now. That was my dance movie, this was my musical.”

The story of Cry-Baby starts back in 1990. The film was released two years after the success of Hairspray and it was so highly anticipated that a bidding war resulted in a budget approximately five times larger than what Waters had used for the previous project.

Loosely inspired by headlines from the Baltimore Sun newspaper, as well as observations of teenage life in Baltimore beyond Waters’ own conservative Catholic upbringing, Cry-Baby is all about the rivalry between the wrong-side-of-the-tracks ‘drapes’ and the clean-cut ‘squares’.

Waters remembered seeing the way that drapes — a subculture born of socioeconomic disadvantage, perhaps better known as ‘greasers’ — were portrayed in the media during his childhood and felt a strong sense of injustice. In particular, he recalled the way that the unsolved 1954 murder of a young teenager, Carolyn Wasilewski, was generally dismissed in the press as a result of her own recklessness.

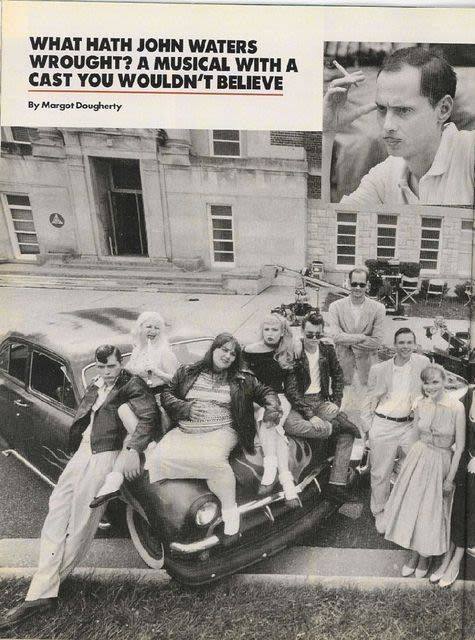

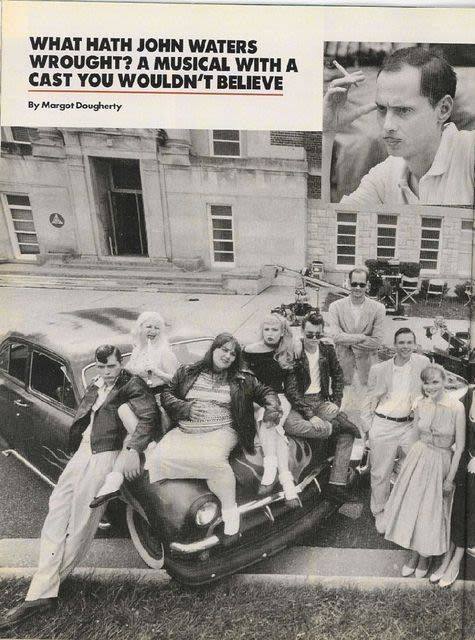

Article from a 1989 issue of People magazine

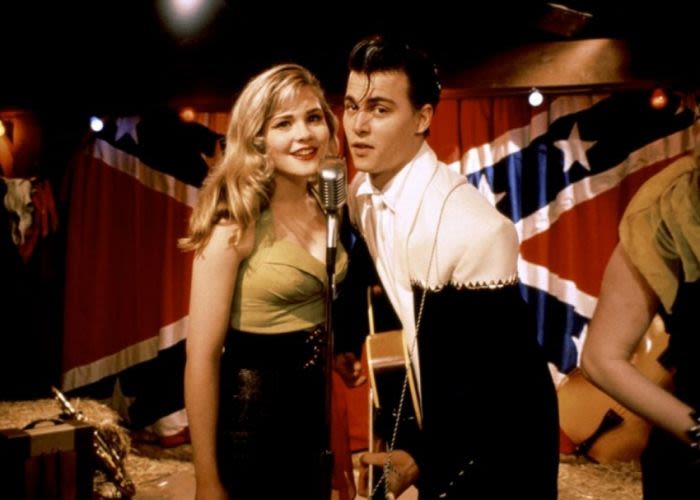

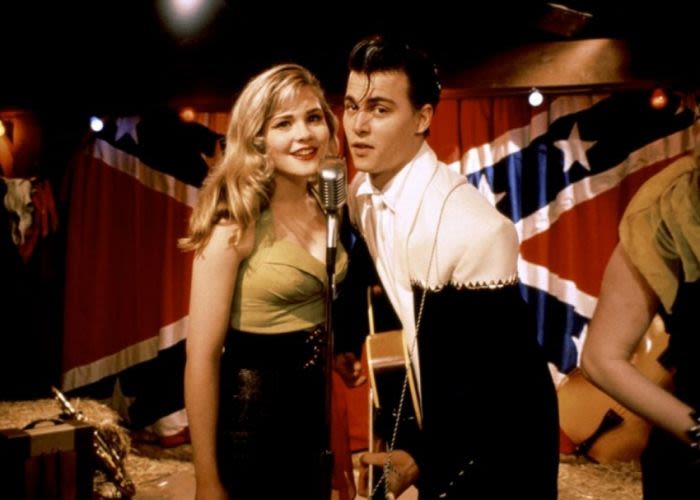

While the film was certainly occupied with some fun riffing on stereotypes of the 1950s and a love story between its two protagonists, Allison Vernon-Williams (Amy Locane) and drape “Cry-Baby” Wade Walker (Johnny Depp), it also harbours elements that are deeply critical and subversive.

Which is, of course, what any reasonable person would expect of a John Waters creation.

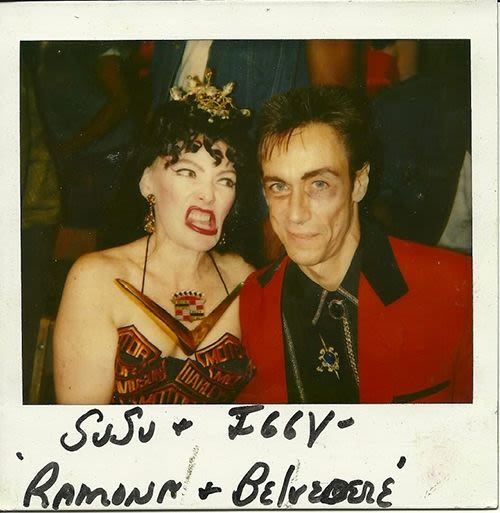

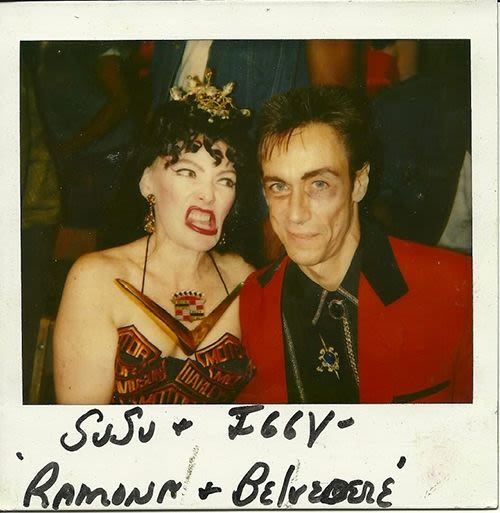

Cry-Baby was a passive aggressive twist on mid-century nostalgia that takes shots at social conservatism, expectations of femininity, and the stifling value systems of the highly privileged. The casting alone indicated Waters’ rebellious intentions. Besides casting Iggy Pop and controversial porn star Traci Lords (who was served a subpoena by the FBI on set), Johnny Depp only agreed to come on board on the basis that the role would mock the stereotype of the sullen teen heartthrob that he was rapidly becoming recognised as.

Polaroid of Susan Tyrell and Iggy Pop

While its aesthetics, music, and odd-ball moments have made Cry-Baby iconic, it failed to live up to commercial expectations. Following its release, it quickly became clear that Cry-Baby was not going to be a success like the musical that came before it.

It earned generally positive reviews but there was some steep criticism too. Roger Ebert gave it three out of four stars but the LA Times review from Peter Rainer read that watching it “is a bit like checking out a grade-school talent show on parents’ night”. And yet, like a lot of John Waters creations, Cry-Baby has become a cult sensation, the ‘anti-Grease’ if you will, loved for its rudeness, cheek and sense of fun.

Article from a 1989 issue of People magazine

Article from a 1989 issue of People magazine

Polaroid of Susan Tyrell and Iggy Pop

Polaroid of Susan Tyrell and Iggy Pop

In 2006, the project to take Cry-Baby to Broadway kicked off. Based on the film but not exactly married to it, the book for the musical was a combined effort between late comedic writer Mark O’Donnell and playwright Thomas Meehan. Meanwhile, the score was taken on by musician Adam Schlesinger and comedy writer David Javerbaum – who’s perhaps best known as executive producer for The Daily Show with Jon Stewart and a viral Twitter account where he tweets as God.

Adam Schlesigner is beloved in certain circles. Best known as the lead singer of Fountains of Wayne, he was also nominated for an Oscar in 1997 for his musical contributions to Tom Hanks’ directorial debut That Thing You Do. Javerbaum said he had never met Schlesinger before being called in to work with him on this project and, initially, he was unsure of how their creative relationship would work out.

“At first it was awkward because I didn’t realise that he saw our collaboration as one where he could work on lyrics and I could also contribute to the music … once I realised that he wasn’t being territorial, he was being practical and helpful and his only desire was for the show to be as good as possible, we got along like gangbusters.”

Javerbaum and Shlesinger went on to work together closely, and incredibly successfully, for another 13 years, until Schlesinger passed away early last year, aged 52, from complications associated with COVID-19.

David Javerbaum and Adam Schlesinger received a 2012 Emmy Award for Outstanding Music And Lyrics for their song "It's Not Just for Gays Anymore", performed by Neil Patrick Harris at the 65th Tony Awards.

David Javerbaum and Adam Schlesinger received a 2012 Emmy Award for Outstanding Music And Lyrics for their song "It's Not Just for Gays Anymore", performed by Neil Patrick Harris at the 65th Tony Awards.

Cry-Baby the Musical on Broadway. Image: Joan Marcus

Cry-Baby the Musical on Broadway. Image: Joan Marcus

While the Cry-Baby Broadway production reflected the tone of the original film, it incorporated elements that were far more challenging and even occasionally weird, like an opening number that involves a teenage boy singing in an iron lung.

Waters wasn’t heavily involved in the project but he had a certain amount of oversight and Javerbaum said he was pleased with the production.

“He was kind of like the presiding genius, the presiding spirit over it. He would come by from time to time and he liked everything we did.”

While Cry-Baby the musical received some high-profile accolades after it officially opened in 2008, such as Tony nominations for its book, choreography, and score, it also received some high-profile panning.

The New York Times critic Ben Brantley dubbed it “tasteless”, saying that the show was “in search of an identity that has all the saliva-stirring properties of week-old pre-chewed gum”.

“It was a huge, huge bummer,” said Javerbaum.

He said a lot of the problems with the production came from a general failure to commit to the frivolous personality of the story.

“The way that a really funny play or movie is, that’s what we were going for. Just really, really funny in an unpredictable and slightly snarky way … I think if anything, I wish we’d have leaned into that a lot more.”

2018 Australian production of Cry-Baby The Musical. Image: Robert Catto.

2018 Australian production of Cry-Baby The Musical. Image: Robert Catto.

2018 Australian production of Cry-Baby The Musical. Image: Robert Catto.

2018 Australian production of Cry-Baby The Musical. Image: Robert Catto.

2018 Australian production of Cry-Baby The Musical. Image: Robert Catto.

2018 Australian production of Cry-Baby The Musical. Image: Robert Catto.

2018 Australian production of Cry-Baby The Musical. Image: Robert Catto.

2018 Australian production of Cry-Baby The Musical. Image: Robert Catto.

But if Cry-Baby is proof of anything it’s that, much like a cat, a story can have nine lives. Javerbaum loved the recent Australian iteration from director Alexander Berlage.

“I wish this had been the Broadway production because this production looks colourful and dynamic and young and hip.”

If reviews and awards are anything to go by, Javerbaum was proven right. The Australian course-correction, which first played the Hayes Theatre in 2018, was successful with audiences and critics. It also won a number of awards since it was first run in 2018, including Best Direction of a Musical and Best Production of a Musical at the Sydney Theatre Awards.

Set designer Isabel Hudson, who previously worked with Berlage on the American Psycho: The Musical production, said that there’s a “candidness and queerness” to Cry-Baby that the team wanted to explore with this latest iteration.

“I think that is just inherently part of the story and the way it’s written and we’ve taken that and staged it.”

Hudson also believes that the production has benefited from an Australian lens in terms of the way that humour translates to an audience here.

“It’s not delivered in an earnest way, which is what I think a lot of what the American version probably did, it probably leant into the stakes of the show,” she said.

“Australians have a very particular brand of humour and I think that it actually really lends itself to people like John Waters because it makes fun of itself in its own way.”