In a jealous fit of bitter rage, frustrated composer Antonio Salieri poisoned his creative rival Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart with arsenic, only to face eternal damnation as a god-fearing man, ensuring the younger man’s place in eternity at the cost of his legacy.

Only this almost certainly never happened. But why let the truth get in the way of a good story? The vicious rumours that swirled around the Habsburg court after Mozart’s untimely death, aged only 35, on December 5th, 1791, have inspired creative genius.

In this edition of Stage Direction, Stephen A Russell delves into the irresistible appeal of a feverishly imagined operatic tragedy.

“It offers the best of what the Opera House can offer – music, opera and theatre. There will be great performances, of course. But at its heart, it’s a great story, set to some of the best music ever written and all wrapped up in a visual feast.”

Who were Mozart and Salieri?

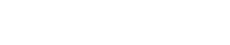

Johann Chrysostom Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart was born on January 27, 1756, in the Austrian city of Salzburg, then encompassed by the Holy Roman Empire. He and his sister Maria Anna were the only survivors of Leopold and Anna Maria’s seven children.

Musically gifted from the outset, Mozart played the harpsichord adeptly by age three, prompting the family to decamp to Vienna, then the artistic centre of Europe, when he was still a teenager. Flourishing professionally and travelling extensively, his excellence across genres led him to a cushy job at the Habsburg court. He was technically second fiddle to the imperious Antonio Salieri, whose high standing at court and popular career ensured that he was more ‘successful’ on paper.

A deeply religious man, Salieri saw divinity in the beauty of music. It’s possible that he was jealous of Mozart reaching closer. No one truly believes, however, that he murdered the younger man. Mozart’s medical records suggest he fell foul of bad luck and ill health. Indeed, Mozart’s widow Constanze, a staunch protector of her late husband’s legacy, remained close to Salieri, who guided her son, Franz, in musical lessons.

Despite Mozart’s fate, buried in a mass grave as was the custom for his social standing, his music has thrummed through the ages undimmed, eclipsing that of Salieri’s despite the latter living until the ripe old age of 74.

In most languages, writing is a complement to speech or spoken language. Writing is not a language but a form of technology. Within a language system, writing relies on many of the same structures as speech, such as vocabulary, grammar and semantics, with the added dependency of a system of signs or symbols, usually in the form of a formal alphabet. The result of writing is generally called text, and the recipient of text is called a reader. Motivations for writing include publication, storytelling, correspondence and diary. Writing has been instrumental in keeping history, dissemination of knowledge through the media and the formation of legal systems.

Wolfgang Mozart Amadeus. Image: Barbara Krafft (Wikimedia Commons)

Wolfgang Mozart Amadeus. Image: Barbara Krafft (Wikimedia Commons)

Antonio Salieri. Image: Joseph Willibrord Mähler (Wikimedia Commons)

Antonio Salieri. Image: Joseph Willibrord Mähler (Wikimedia Commons)

“We were both ordinary men, he and I.

Yet from the ordinary he created legends!”

From scandalous rumours to the stage

Russian literary giant Alexander Sergeyevich Pushkin first saw potential in the half-truths that swirled around these great men. He penned Mozart and Salieri – one of four short plays collectively known as The Little Tragedies – in 1830. It revels in their imagined rivalry.

Seizing on Salieri’s poisonous possibility, Pushkin was onto something big. Mozart and Salieri introduces the formidable idea of man’s despair at being abandoned by his God, with something of the Faustian pact in Salieri seeking to destroy the greatness he coveted. It’s a theme that would profoundly influence Tolstoy and Dostoevsky. There are parallels, too, with artistic suppression in Russia at the time, as led by Tsars Alexander I and Nicholas I.

A diabolically good story, it would inspire Russian composer Nikolai Rimsky-Korsakov to spin it into an opera by the same name, bowing in 1897. Much later still, Pushkin’s work captured the imagination of Liverpool-born writer Peter Shaffer, who would pen his masterpiece Amadeus in 1979.

“Pushkin took some liberties with the truth,” says Craig Ilott, director of the Sydney Opera House’s re-staging of Amadeus. “But by the time that Shaffer went on a deep dive through historical research, he said it was a little too late.”

Alexander Sergeyevich Pushkin. Image: Vasily Andreevich Tropinin (Wikimedia Commons)

Alexander Sergeyevich Pushkin. Image: Vasily Andreevich Tropinin (Wikimedia Commons)

“By then, the cold eyes of Salieri were staring at me....

The conflict between virtuous mediocrity and feckless genius took hold of my imagination, and it would not leave me alone.”

Too bad not to be good

Shaffer was swept up in the wicked possibility of Pushkin’s framing, also opting to frame Amadeus as a murderous confession. Who could resist the drama, Ilott asks?

“I thought that was just a beautiful thing, because the conflict between those two striking figures is obviously the key,” he says of the late Shaffer’s play. “I read it as a uni student many years ago, and it’s never really left me. There’s this everyman [Salieri], a small-town Catholic kid who had an artistic dream that he would take off as a great composer with God on his side. And then he comes across the revelation that is Mozart.

“What would it be like to feel, as an artist, that you only have enough ability to recognise somebody else’s genius? It tortured Salieri,” Ilott says.

It’s the sort of juicy conflict that makes for impeccable drama. Audiences lapped it up when it debuted at the National Theatre in London in November 1979. Simon Callow played Mozart to Paul Scofield’s Salieri, with Felicity Kendal as Constanze. Transferring to the West End, it then hopped over to Broadway, where Ian McKellen played Salieri to Tim Curry’s Mozart and Jayne Seymour’s Constanze. That production secured the Tony Award for Best Play in 1981.

But that wasn’t the end of this story’s success. Revered Czech filmmaker Miloš Forman would tap Shaffer to adapt his play for the big-budget 1984 movie. Starring F. Murray Abraham as Salieri, Tom Hulce as Mozart and Elizabeth Berridge as Constanze, it scooped up eight Oscars the following year, including one for Shaffer’s screenplay.

“It’s such a striking piece,” Ilot recalls of seeing it on the big screen as a young man.

Jane Seymour (Constanze Mozart) and Ian McKellen (Antonio Salieri) in Amadeus on Broadway

Jane Seymour (Constanze Mozart) and Ian McKellen (Antonio Salieri) in Amadeus on Broadway

“Salieri is, in effect, saying that if Mozart’s music is the voice of God, then that has rendered his twee and pointless, and that starts this great conflict between him and Mozart, which quickly becomes a battle between Salieri and his God.”

From Rockhampton to the Opera House

Amadeus director Craig Ilott first fell in love with the theatrical form as a small-town boy from Rockhampton, when the legendary Baz Luhrmann rolled into town in 1986, six years before Strictly Ballroom would debut to international acclaim. Luhrmann cast Ilott as the young lead in the community musical Crocodile Creek. “I was in year 12 and Baz made such an impression on me,” he says.

The bug well and truly caught, Ilott went on to study at NIDA, where he first encountered Shaffer’s plays, devouring Amadeus. “I’ve never seen it performed live, only the film,” he reveals.

Amadeus revels in the intertextual, with scenes encompassing performances of Mozart operas, including Don Giovanni, The Marriage of Figaro, and The Magic Flute. It’s the perfect spectacle, then, to welcome audiences back to the newly renovated Concert Hall during the Opera House’s 50th-anniversary celebrations.

Michael Sheen (The Queen) steps into Salieri’s fine shoes, having previously portrayed Mozart opposite Poirot actor David Suchet at London’s Old Vic theatre in 1998. “Michael knows the power and the play, and he wants to live the other side of it,” Ilott says.

Fast-rising Australian star Rahel Romahn (Here Out West, Shantaram) plays Mozart, with Lily Balatincz (Constellations, Stop the Virgens) as Constanze, alongside a massive cast of actors, opera singers and an on-stage orchestra. Even as an award-winning director who has staged extravaganzas from rock musical Hedwig and the Angry Inch to Puccini opera La Boehme, Ilott can hardly believe his luck in bringing Amadeus back to life during the Opera House celebrations. “It’s certainly the most ambitious production I’ve been a part of.”

Looking the part

There’s an incredible team behind the new staging. Award-winning set and costume designer Anna Cordingley teamed up with Luke Sales and Anna Plunkett of celebrated fashion house Romance Was Born to bring a contemporary twist to the look and feel of this all-stop-pulled-out production of Amadeus.

“It’s such an ambitious work, because we’re picking up on these phrases from Mozart operas like The Magic Flute, Così, and there are little notes from Don Giovanni too,” Cordingley says. “It’s this big and bold and crazy thing, celebrating the birthday of the Opera House, with all these layers woven into it.

“Collaborating with Romance Was Born has been such a joy,” Cordingley adds. “I’m working with real artists, and they are beautiful.

Sales is equally complimentary, noting that Cordingley helped guide him and Plunkett through the practicalities of a massive stage production. Their costumes are highly stylized takes on the frocks that were de rigueur at the Habsburg court. “We like to push the envelope a bit, with an element of escapism and fantasy,” Sales says, “so we’re trying to get away with as much as possible.”

Amadeus also covers an extended timeframe, necessitating more costume changes. “Everyone’s bought something a little bit different,” Sales says.

Image: Daniel Boud

Image: Daniel Boud

Rahel Romahn and Lily Balatincz as Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart and Constanze Mozart. Image: Daniel Boud

Rahel Romahn and Lily Balatincz as Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart and Constanze Mozart. Image: Daniel Boud

“Craig is my jam as a director, because he has the vision for the aesthetics, and an intuitive understanding of the complexities of these characters… The trap is, when you’re dealing with historical figures, that they can become a little rigid, almost like caricatures. Craig has the emotional intelligence and instincts to let us explore all their different colours and not just have them be a puppet of history.”

Image: Daniel Boud

Image: Daniel Boud

Image: Daniel Boud

Image: Daniel Boud

Big shoes to fill

Rahel Romahn chooses not to be overwhelmed stepping into the role that scored Michael Sheen an Olivier Award nomination. “Am I nervous? Absolutely! But all I can do is see it as exciting that I actually can ask Michael for advice,” he says. “And I think he’s going to bring some tinge of madness and malevolence to the character of Salieri.”

Romahn was a fan of Forman’s film as a teenager, but he has made a conscious effort to put all other productions aside for now and focus on his unique take on Mozart. “It’s such a journey from the minute the play begins to the end that you want to make sure you hit every moment. And I think we have the cast and crew to be able to do that, from the costuming to the lighting, directing and producing.”

Co-star Lily Balatincz is equally awestruck by the scale of the show, and itching to get under Constanze’s skin. “She’s tainted by a lot of biographies as being not worthy of Mozart, but if it weren’t for her being so business-minded – supposedly money hungry – or her organisational skills, her incredible administration after he died, literally signing off on every page of his work with her signature to say this is Mozart’s, we wouldn’t have the catalogue of his works that we do today.”

There’s a strange sense of destiny for Balatincz stepping into this role. Her father, like Mozart, was born in Salzburg. On a recent trip to explore her routes, she also visited Mozart’s grave in Vienna. “Rahel called me at that exact moment,” she says. “It was surreal. He must have picked up on that wavelength. It was serendipitous.”

Romahn cannot wait to welcome audiences back to the Concert Hall alongside Balatincz. “Knowing that I’m going to be on that stage, conducting Mozart’s music, with Lily, Michael, an orchestra and opera singers, it’s otherworldly. Our job is to ensure the audience is just as enthralled and excited as we are.”